- Phakir Chand (Folk-Tales of Bengal) – Part I

- Phakir Chand (Folk-Tales of Bengal) – Part II

- Phakir Chand (Folk-Tales of Bengal) – Part III

In the morning he left the Brahman’s house, went to the outskirts of the city, divested himself of his usual clothing, put round his waist a short and narrow piece of cloth which scarcely reached his knee-joints, rubbed his body well with ashes, took in his hand a twig which he broke off a tree, and thus accoutred, presented himself before the door of the hut of Phakir’s mother.

He commenced operations by dancing, in a most violent manner, to the tune of dhoop! dhoop! dhoop! The dancing attracted the notice of the old woman, who, supposing that her son had come, said—“My son Phakir, are you come? Come, my darling; the gods have at last become propitious to us.” The supposed Phakir Chand uttered the monosyllable “hoom,” and went on dancing in a still more violent manner than before, waving the twig in his hand.

“This time you must not go away,” said the old woman, “you must remain with me.”

“No, I won’t remain, I won’t remain,” said the minister’s son.

“Remain with me, and I’ll get you married to the Rajah’s daughter. Will you marry, Phakir Chand?” The minister’s son replied—“Hoom, hoom,” and danced on like a madman.

“Will you come with me to the Rajah’s house? I’ll show you a princess of uncommon beauty who has risen from the waters.” “Hoom, hoom,” was the answer that issued from his lips, while his feet tripped it violently to the sound of dhoop! dhoop!

“Do you wish to see a manik, Phakir, the crest jewel of the serpent, the treasure of seven kings?” “Hoom, hoom,” was the reply.

The old woman brought it out of the hut the snake-jewel and put it into the hand of her supposed son. The minister’s son took it and carefully wrapped it up in the piece of cloth around his waist. Phakir’s mother, delighted beyond measure at the opportune appearance of her son, went to the Rajah’s house, partly to announce to the Rajah the news of Phakir’s appearance, and partly to show Phakir the princess of the waters.

The supposed Phakir and his mother found ready access to the Rajah’s palace, for the old woman had, since the capture of the princess, become the most important person in the kingdom. She took him into the room where the princess was and introduced him to her. It is superfluous to remark that the princess was by no means pleased with the company of a madcap, who was in a state of semi-nudity, whose body was rubbed with ashes, and who was ever and anon dancing in a wild manner.

At sunset, the old woman proposed to her son that they should leave the palace and go to their own house. But the supposed Phakir Chand refused to comply with the request; he said he would stay there that night. His mother tried to persuade him to return with her, but he persisted in his determination. He said he would remain with the princess. Phakir’s mother therefore went away, after giving instructions to the guards and attendants to take care of her son.

When all in the palace had retired to rest, the supposed Phakir, coming towards the princess, said in his own usual voice—“Princess! do you not recognise me? I am the minister’s son, the friend of your princely husband.”

The princess, astonished at the announcement, said—“Who? The minister’s son? Oh, my husband’s best friend, do rescue me from this terrible captivity, from this worse than death. O fate! it is by my own fault that I am reduced to this wretched state. Oh, rescue me, rescue me, thou best of friends!” She then burst into tears.

The minister’s son said, “Do not be disconsolate. I will try my best to rescue you this very night; only you must do whatever I tell you.”

“I will do anything you tell me, minister’s son; anything you tell me.”

After this, the supposed Phakir left the room and passed through the courtyard of the palace. Some of the guards challenged him, to whom he replied, “Hoom, hoom; I will just go out for a minute and again come in presently.” They understood that it was the madcap Phakir. True to his word he did come back shortly, and went to the princess. An hour afterwards he again went out and was again challenged, on which he made the same reply as at the first time.

The guards who challenged him began to mutter between their teeth—“This madcap of a Phakir will, we suppose, go out and come in all night. Let the fellow alone; let him do what he likes. Who can be sitting up all night for him?”

The minister’s son was going out and coming in with the view of accustoming the guards to his constant egress and ingress, and also of watching for a favourable opportunity to escape with the princess. About three o’clock in the morning the minister’s son again passed through the courtyard, but this time no one challenged him, as all the guards had fallen asleep.

Overjoyed at the auspicious circumstance, he went to the princess. “Now, princess is the time for escape. The guards are all asleep. Mount on my back, tie the locks of your hair round my neck, and keep tight hold of me.”

The princess did as she was told. He passed unchallenged through the courtyard with the lovely burden on his back, passed out of the gate of the palace—no one challenging him passed on to the outskirts of the city and reached the tank from which the princess had risen. The princess stood on her legs, rejoicing at her escape, and at the same time trembling. The minister’s son untied the snake jewel from his waist-cloth and descended into the waters, both he and she found their way to the subterranean palace.

The reception that the prince in the subaqueous palace gave to his wife and his friend may be easily imagined. He had nearly died of grief, but now he suffered a resurrection. The three were now mad with joy. During the three days that they remained in the palace they again and again told the story of the egress of the princess into the upper world, of her seizure, of her captivity in the palace, of the preparations for marriage, of the old woman, of the minister’s son personating Phakir Chand, and of the successful deliverance. It is unnecessary to add that the prince and the princess expressed their gratitude to the minister’s son in the warmest terms, declared him to be their best and greatest friend, and vowed to abide always, till the day of their death, by his advice, and to follow his counsel.

Being resolved to return to their native country, the king’s son, the minister’s son, and the princess left the subterranean palace, and, lighted in the passage by the snake-jewel, made their way good to the upper world. As they had neither elephants nor horses, they were under the necessity of travelling on foot; and though this mode of travelling was troublesome to both the king’s son and the minister’s son, as they were bred in the lap of luxury, it was infinitely more troublesome to the princess, as the stones of the rough road

“Wounded the invisible

Palms of her tender feet where’er they fell.”

When her feet became very sore, the king’s son sometimes took her up on his broad shoulders, on which she sat astride; but the load, however lovely, was too heavy to be carried any great distance. She therefore, for the most part, travelled on foot.

One evening they took shelter beneath a tree, as no human habitations were visible. The minister’s son said to the prince and princess, “Both of you go to sleep, and I will keep watch in order to prevent any danger.” The royal couple were soon locked in the arms of sleep. The faithful son of the minister did not sleep but sat up watching. It so happened that on that tree swung the nest of the two immortal birds, Bihangama and Bihangami, who were not only endowed with the power of human speech but who could see into the future. To the no little astonishment of the minister’s son the two prophetical birds joined in the following conversation:

Bihangama. The minister’s son has already risked his own life for the safety of his friend, the king’s son; but he will find it difficult to save the prince at last.

Bihangami. Why so?

Bihangama. Many dangers await the king’s son. The prince’s father, when he hears of the approach of his son, will send for him an elephant, some horses, and attendants. When the king’s son rides on the elephant he will fall down and die.

Bihangami. But suppose someone prevents the king’s son from riding on the elephant, and makes him ride on horseback, will he not in that case be saved?

Bihangama. Yes, he will in that case escape that danger, but a fresh danger awaits him. When the king’s son is in sight of his father’s palace, and when he is in the act of passing through its lion gate, the lion gate will fall upon him and crush him to death.

Bihangami. But suppose someone destroys the lion gate before the king’s son goes up to it; will not the king’s son in that case be saved?

Bihangama. Yes, in that case, he will escape that particular danger; but a fresh danger awaits him. When the king’s son reaches the palace and sits at a feast prepared for him, and when he takes into his mouth the head of a fish cooked for him, the head of the fish will stick in his throat and choke him to death.

Bihangami. But suppose someone sitting at the feast snatches the head of the fish from the prince’s plate and thus prevents him from putting it into his mouth, Will not the king’s son, in that case, be saved?

Bihangama. Yes, in that case, he will escape that particular danger; but a fresh danger awaits him. When the prince and princess after dinner retire to their sleeping apartment, and they lie together in bed, a terrible cobra will come into the room and bite the king’s son to death.

Bihangami. But suppose someone lying in wait in the room cut the snake into pieces, will not the king’s son in that case be saved?

Bihangama. Yes, in that case, the life of the king’s son will be saved; but if the man who kills the snake repeats to the king’s son the conversation between you and me, that man will be turned into a marble statue.

Bihangami. But is there no means of restoring the marble statue to life?

Bihangama. Yes, the marble statue may be restored to life if it is washed with the life-blood of the infant which the princess will give birth to, immediately after it is ushered into the world.

The conversation of the prophetical birds had extended thus far when the crows began to caw, the east put on a reddish hue, and the travellers beneath the tree bestirred themselves. The conversation stopped, but the minister’s son had heard it all.

The prince, the princess, and the minister’s son pursued their journey in the morning; but they had not walked many hours when they met a procession consisting of an elephant, a horse, a palki, and a large number of attendants.

These animals and men had been sent by the king, who had heard that his son, together with his newly married wife and his friend the minister’s son, were not far from the capital on their journey homewards. The elephant, which was richly caparisoned, was intended for the prince; the palki the framework of which was silver and was gaudily adorned, was meant for the princess; and the horse for the minister’s son.

As the prince was about to mount on the elephant, the minister’s son went up to him and said—“Allow me to ride on the elephant, and you please ride on horseback.” The prince was not a little surprised at the coolness of the proposal. He thought his friend was presuming too much on the services he had rendered; he was therefore nettled, but remembering that his friend had saved both him and his wife, he said nothing, but quietly mounted the horse, though his mind became somewhat alienated from him.

The procession started, and after some time came in sight of the palace, the lion gate of which had been gaily adorned for the reception of the prince and the princess. The minister’s son told the prince that the lion gate should be broken down before the prince could enter the palace. The prince was astounded at the proposal, especially as the minister’s son gave no reasons for so extraordinary a request. His mind became still more estranged from him; but in consideration of the services the minister’s son had rendered, his request was complied with, and the beautiful lion-gate, with its gay decorations, was broken down.

The party now went into the palace, where the king gave a warm reception to his son, his daughter-in-law, and to the minister’s son. When the story of their adventures was related, the king and his courtiers expressed great astonishment, and they all with one voice extolled the sagacity, prudence, and devotedness of the minister’s son. The ladies of the palace were struck with the extraordinary beauty of the new-comer; her complexion was milk and vermilion mixed together; her neck was like that of a swan; her eyes were like those of a gazelle; her lips were as red as the berry bimba; her cheeks were lovely; her nose was straight and high; her hair reached her ankles; her walk was as graceful as that of a young elephant—such were the terms in which the connoisseurs of beauty praised the princess whom destiny had brought into the midst of them. They sat around her and asked her a thousand questions regarding her parents, the subterranean palace in which she formerly lived, and the serpent that had killed all her relatives.

It was now time for the new arrivals should have their dinner. The dinner was served up in dishes of gold. All sorts of delicacies were there, amongst which the most conspicuous was the large head of a rohita fish placed in a golden cup near the prince’s plate. While they were eating, the minister’s son suddenly snatched the head of the fish from the prince’s plate, and said, “Let me, prince, eat this rohita’s head.” The king’s son was quite indignant. He said nothing, however. The minister’s son perceived that his friend was in a terrible rage; but he could not help it, as his conduct, however strange, was necessary to the safety of his friend’s life; neither could he clear himself by stating the reason for his behaviour, as in that case he himself would be transformed into a marble statue.

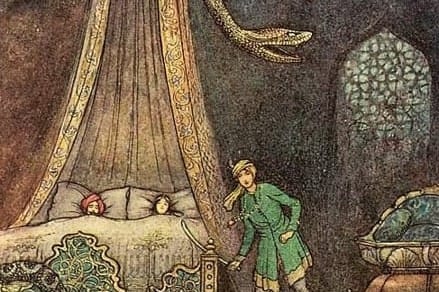

The dinner was over, and the minister’s son expressed his desire to go to his own house. At other times the king’s son would not allow his friend to go away in that fashion; but being shocked at his strange conduct, he readily agreed to the proposal. The minister’s son, however, had not the slightest notion of going to his own house; he was resolved to avert the last peril that was to threaten the life of his friend. Accordingly, with a sword in his hand, he stealthily entered the room in which the prince and the princess were to sleep that night and ensconced himself under the bedstead, which was furnished with mattresses of down and canopied with mosquito curtains of the richest silk and gold lace.

Soon after dinner the prince and princess came into the bedroom, and undressing themselves went to bed. At midnight, while the royal couple were asleep, the minister’s son perceived a snake of gigantic size enter the room through one of the water-passages, and climb up the tester-frame of the bed. He rushed out of his hiding place, killed the serpent, cut it up in pieces, and put the pieces in the dish for holding betel leaves and spices.

It so happened, however, that as the minister’s son was cutting the serpent into pieces, a drop of blood fell on the breast of the princess, and the rather as the mosquito curtains had not been let down. Thinking that the drop of blood might injure the fair princess, he resolved to lick it up. But as he regarded it as a great sin to look upon a young woman lying asleep half naked, he blindfolded himself with seven-fold cloth and licked up the drop of blood. But while he was in the act of licking it, the princess awoke and screamed, and her scream roused her husband lying beside her. The prince seeing the minister’s son, who he thought had gone away to his own house, bending over the body of his wife, fell into a great rage, and would have got up and killed him, had not the minister’s son brought him to restrain his anger, adding—“Friend, I have done this only in order to save your life.”

“I do not understand what you mean,” said the prince; “ever since we came out of the subterranean palace you have been behaving in a most extraordinary way. In the first place, you prevented me from getting upon the richly caparisoned elephant, though my father, the king, had purposely sent it for me. I thought, however, that a sense of the services you had rendered to me had made you exceedingly vain; I, therefore, let the matter pass and mounted the horse. In the second place, you insisted on the destruction of the fine lion-gate, which my father had adorned with gay decorations; and I let that matter also pass. Then, again, at dinner, you snatched away, in a most shameful manner, the rohita’s head which was on my plate, and devoured it yourself, thinking, no doubt, that you were entitled to higher honours than I. You then pretended that you were going home, for which I was not at all sorry, as you had made yourself very disagreeable to me. And now you are actually in my bedroom, bending over the naked bosom of my wife. You must have had some evil design, and you pretend that you have done this to save my life. I fancy it was not for saving my life, but for destroying my wife’s chastity.”

“Oh, do not harbour such thoughts in your mind against me. The gods know that I have done all this for the preservation of your life. You would see the reasonableness of my conduct throughout if I had the liberty of stating my reasons.”

“And why are you not at liberty?” asked the prince; “Who has shut up your mouth?”

“It is destiny that has shut up my mouth,” answered the minister’s son; “if I were to tell it all, I should be transformed into a marble statue.”

“You would be transformed into a marble statue!” exclaimed the prince; “you must take me to be a simpleton to believe this nonsense.”

“Do you wish me then, friend,” said the minister’s son, “to tell you all? You must then make up your mind to see your friend turned into stone.”

“Come, out with it,” said the prince, “or else you are a dead man.” The minister’s son, in order to clear himself of the foul accusation brought against him, deemed it his duty to reveal the secret at the risk of his life. He again and again warned the prince not to press him. But the prince remained inexorable.

The minister’s son then went on to say that, while bivouacking under a lofty tree one night, he had overheard a conversation between Bihangama and Bihangami, in which the former predicted all the dangers that were to threaten the life of the prince. When the minister’s son had related the prediction concerning the mounting of the elephant, his lower parts were turned into stone. He then, turning to the prince, said, “See, friend, my lower parts have already turned into stone.”

“Go on, go on,” said the prince, “with your story.”

The minister’s son then related the prophecy regarding the destruction of the lion gate, when half of his body was converted into stone. He then related the prediction regarding the eating of the head of the fish, when his body up to his neck was petrified. “Now, friend,” said the minister’s son, “the whole of my body, except my neck and head, is petrified; if I tell the rest, I shall assuredly become a man of stone. Do you wish me still to go on?”

“Go on,” answered the prince, “go on.”

“Very well, I will go on to the end,” said the minister’s son; “but in case you repent after I have become turned into stone, and wish me to be restored to life, I will tell you of the manner in which it may be effected. The princess after a few months will be delivered of a child; if immediately after the birth of the infant you kill it and besmear my marble body with its blood, I shall be restored to life.” He then related the prediction regarding the serpent in the bedroom; and when the last word was on his lips the rest of his body was turned into stone, and he dropped on the floor a marble image.

The princess jumped out of bed, opened the vessel for betel leaves and spices, and saw there pieces of a serpent. Both the prince and the princess now became convinced of the good faith and benevolence of their departed friend. They went to the marble figure, but it was lifeless. They set up a loud lamentation; but it was to no purpose, for the marble moved not. They then resolved to keep the marble figure concealed in a safe place and to besmear it with the blood of their firstborn child when it should be ushered into existence.

In the process of time, the hour of the princess’s travail came on, and she was delivered a beautiful boy, the perfect image of his mother. Both father and mother were struck with the beauty of their child, and would fain have spared its life; but recollecting the vows they had made on behalf of their best friend, now lying in a corner of the room a lifeless stone, and the inestimable services he had rendered to both of them, they cut the child into two, and besmeared the marble figure of the minister’s son with its blood. The marble became animated in a moment. The minister’s son stood before the prince and princess, who became exceedingly glad to see their old friend again in life. But the minister’s son, who saw the lovely newborn babe lying in a pool of blood, was overwhelmed with grief. He took up the dead infant, carefully wrapped it up in a towel, and resolved to get it restored to life.

The minister’s son, intent on the reanimation of his friend’s child, consulted all the physicians of the country; but they said that they would undertake to cure any person of any disease so long as life was in him, but when life was extinct, the case was beyond their jurisdiction.

The minister’s son at last bethought himself of his own wife, who was living in a distant town, and who was a devoted worshipper of the goddess Kali, who, through his wife’s intercession, might be prevailed upon to give life to the dead child. He, accordingly, set out on a journey to the town in which his wife was living in her father’s house. Adjoining that house there was a garden where upon a tree he hung the dead child wrapped up in a towel.

His wife was overjoyed to see her husband after so long a time; but to her surprise, she found that he was very melancholy, that he spoke very little, and that he was brooding over something in his mind. She asked the reason for his melancholy, but he kept quiet.

One night while they were lying together in bed, the wife got up and opening the door went out. The husband, who had little sleep any night in consequence of the weight of anxiety regarding the reanimation of his friend’s child, perceiving his wife going out at that dead hour of the night, determined to follow her without being noticed. She went to a temple of the goddess Kali, which was at no great distance from her house. She worshipped the goddess with flowers and sandalwood perfume, and said, “O mother Kali! have mercy upon me, and deliver me out of all my troubles.”

The goddess replied, “Why, what further grievance have you? You long prayed for the return of your husband, and he has returned; what aileth thee now?”

The woman answered, “True, O Mother, my husband has come to me, but he is very moody and melancholy, hardly speaks to me, takes no delight in me, only sits moping in a corner.”

To which the goddess rejoined, “Ask your husband what the reason for his melancholy is, and let me know it.”

The minister’s son overheard the conversation between the goddess and his wife, but he did not make his appearance; he quietly slunk away before his wife and went to bed. The following day the wife asked her husband of the cause of his melancholy, and he related all the particulars regarding the killing of the infant child of the prince.

The next night at the same dead hour the wife proceeded to Kali’s temple and mentioned to the goddess the reason for her husband’s melancholy; to which the goddess said, “Bring the child here and I will restore it to life.” On the succeeding night, the child was produced before the goddess Kali, and she called it back to life. Entranced with joy, the minister’s son took up the reanimated child, went as fast as his legs could carry him to the prince and princess, and presented to them their child alive and well. They all rejoiced with exceeding great joy and lived together happily till the day of their death.

Thus my story endeth,

The Natiya-thorn withereth, etc.