- The Adventures of Two Thieves and of their Son (Folk-tales of Bengal) – I

- The Adventures of Two Thieves and of their Son (Folk-tales of Bengal) – II

Once upon a time, there lived two thieves in a village who earned their livelihood by stealing. As they were well-known thieves, every act of theft in the village was ascribed to them whether they committed it or not; they therefore left the village, and, being resolved to support themselves by honest labour, went to a neighbouring town for service.

Both of them were engaged by a householder; one had to tend a cow, and the other to water a champaka plant. The elder thief began watering the plant early in the morning, and as he had been told to go on pouring water till some of it collected itself round the foot of the plant he went on pouring bucketful after bucketful: but to no purpose.

No sooner was the water poured on the foot of the plant than it was forthwith sucked up by the thirsty earth; and it was late in the afternoon when the thief, tired of drawing water, laid himself down on the ground and fell asleep. The younger thief fared no better. The cow which he had to tend was the most vicious in the whole country. When taken out of the village for pasturage it galloped away to a great distance with its tail erect; it ran from one paddy field to another, ate the corn and trod upon it; it entered into sugar-cane plantations and destroyed the sweet cane;—for all which damage and acts of trespass the neatherd was soundly rated by the owners of the fields. What with running after the cow from field to field, from pool to pool; what with the abusive language poured not only upon him but upon his forefathers up to the fourteenth generation, by the owners of the fields in which the corn had been destroyed,—the younger thief had a miserable day of it. After a world of trouble, he succeeded about sunset in catching hold of the cow, which he brought back to the house of his master. The elder thief had just roused himself from sleep when he saw the younger one bringing in the cow.

Then the elder said to the younger—”Brother, why are you so late in coming from the fields?”

Younger. What shall I say, brother? I took the cow to that part of the meadow where there is a tank, near which there is a large tree. I let the cow loose, and it began to graze about without giving the least trouble. I spread my gamchha ( A towel used in bathing) upon the grass under the tree, and there was such a delicious breeze that I soon fell asleep, I did not wake till after sunset, and when I awoke I saw my good cow grazing contentedly at the distance of a few paces. But how did you fare, brother?

Elder. Oh, as for me, I had a jolly time of it. I had poured only one bucketful of water on the plant when a large quantity rested around it. So my work was done, and I had the whole day to myself. I laid myself down on the ground; I meditated on the joys of this new mode of life; I whistled; I sang; and at last fell asleep. And I am up only this moment.

When this talk ended, the elder thief, believing that what the younger thief had said was true, thought that tending the cow was more comfortable than watering the plant; and the younger thief, for the same reason, thought that watering the plant was more comfortable than tending the cow: each therefore resolved to exchange his own work for that of the other.

Elder. Well, brother, I have a wish to tend the cow. Suppose tomorrow you take my work, and I yours. Have you any objections?

Younger. Not the slightest, brother. I shall be glad to take up your work, and you are quite welcome to take up mine. Only let me give you a bit of advice. I felt it rather uncomfortable to sleep nearly the whole of the day on the bare ground. If you take a charpoy (A sort of bed made of rope, supported by posts of wood) with you, you will have a merry time of it.

Early the following morning the elder thief went out with the cow to the fields, not forgetting to take with him a charpoy for his ease and comfort; and the younger thief began watering the plant. The latter had thought that one bucketful, or at the outside two bucketfuls, of water would be enough. But what was his surprise when he found that even a hundred bucketfuls were not sufficient to saturate the ground around the roots of the plant? He was dead tired of drawing water. The sun was almost going down, and yet his work was not over. At last, he gave it up through sheer weariness.

The elder thief in the fields was in no better case. He took the cow beside the tank that the younger thief had spoken of, put his charpoy under the large tree hard by, and then let the cow loose. As soon as the cow was let loose it went scampering about in the meadow, jumping over hedges and ditches, running through paddy fields, and injuring sugarcane plantations. The elder thief was not a little put about. He had to run about the whole day, and to be insulted by the people whose fields had been trespassed upon. But the worst of it was, that our thief had to run about the meadow with the charpoy on his head, for he could not put it anywhere for fear it should be taken away. When the other neatherds who were in the meadow saw the elder thief running about in breathless haste after the cow with the charpoy on his head, they clapped their hands and raised shouts of derision. The poor fellow, hungry and angry, bitterly repented of the exchange he had made. After infinite trouble, and with the help of the other neatherds, he at last caught hold of the precious cow, and brought it home long after the village lamps had been lit.

When the two thieves met in the house of their master, they merely laughed at each other without speaking a word. Their dinner over, they laid themselves to rest, when there took place the following conversation:—

Younger. Well, how did you fare, brother?

Elder. Just as you fared, and perhaps some degrees better.

Younger. I am of the opinion that our former trade of thieving was infinitely preferable to this sort of honest labour, as people call it.

Elder. What doubt is there of that? But, by the gods, I have never seen a cow that can be compared to this. It has no second in the world in point of viciousness.

Younger. A vicious cow is not a rare thing. I have seen some cows as vicious. But have you ever seen a plant like this champaka plant which you were told to water? I wonder what becomes of all the water that is poured round about it. Is there a tank below its roots?

Elder. I have a good mind to dig around it and see what is beneath it.

Younger. We had better do so this night when the good man of the house and his wife are asleep.

At about midnight the two thieves took spades and shovels and began digging around the plant. After digging a good deal the younger thief lighted upon some hard thing against which the shovel struck. The curiosity of both was excited. The younger thief saw that it was a large jar; he thrust his hand into it and found that it was full of gold mohurs.

But he said to the elder thief—”Oh, it is nothing; it is only a large stone.”

The elder thief, however, suspected that it was something else; but he took care not to give vent to his suspicion. Both agreed to give up digging as they had found nothing, and they went to sleep.

An hour or two later, when the elder thief saw that the younger thief was asleep, he quietly got up and went to the spot that had been dug. He saw the jar filled with gold mohurs. Digging a little near it, he found another jar also filled with gold mohurs. Overjoyed to find the treasure, he resolved to secure it. He took up both the jars, went to the tank which was near, and from which water used to be drawn for the plant, and buried them in the mud of its bank. He then returned to the house and quietly laid himself down beside the younger thief, who was then fast asleep.

The younger thief, who had first found the jar of gold mohurs, now woke, and softly stealing out of bed, went to secure the treasure he had seen. On going to the spot he did not see any jar; he therefore naturally thought that his companion the elder thief had secreted it somewhere. He went to his sleeping partner, with a view to discover if possible by any marks on his body the place where the treasure had been hidden. He examined the person of his friend with the eye of a detective and saw mud on his feet and near the ankles. He immediately concluded the treasure must have been concealed somewhere in the tank. But in what part of the tank? on which bank? His ingenuity did not forsake him here. He walked round all the four banks of the tank. When he walked around three sides, the frogs on them jumped into the water; but no frogs jumped from the fourth bank. He therefore concluded that the treasure must have been buried on the fourth bank. In a little he found the two jars filled with gold mohurs; he took them up, and going into the cow-house brought out the vicious cow he had tended, and put the two jars on its back. He left the house and started for his native village.

When the elder thief at crow-cawing got up from sleep, he was surprised not to find his companion beside him. He hastened to the tank and found that the jars were not there. He went to the cow’s house and did not see the vicious cow. He immediately concluded the younger thief must have run away with the treasure on the back of the cow. And where could he think of going? He must be going to his native village. No sooner did this process of reasoning pass through his mind than he resolved forthwith to set out and overtake the younger thief.

As he passed through the town, he invested all the money he had in a costly pair of shoes covered with gold lace. He walked very fast, avoiding the public road and taking shortcuts. He descried the younger thief trudging on slowly with his cow. He went before him on the highway about a distance of 200 yards and threw down on the road one shoe. He walked another 200 yards and threw the other shoe at a place near which was a large tree; amid the thick leaves of that tree, he hid himself.

The younger thief coming along the public road saw the first shoe and said to himself—”What a beautiful shoe that is! It is of gold lace. It would have suited me in my present circumstances now that I have become rich. But what shall I do with one shoe?” So he passed on. In a short time, he came to the place where the other shoe was lying. The younger thief said to himself—”Ah, here is the other shoe! What a fool I was, that I did not pick up the one I first saw! However it is not too late, I’ll tie the cow to yonder tree and go for the other shoe.”

He tied the cow to the tree, and taking up the second shoe went for the first, lying at a distance of about 200 yards. In the meantime the elder thief got down from the tree, loosened the cow, and drove it towards his native village, avoiding the king’s highway. The younger thief on returning to the tree found that the cow was gone. He of course concluded that it could have been done only by the elder thief. He walked as fast as his legs could carry him and reached his native village long before the elder thief with the cow.

He hid himself near the door of the elder thief’s house. The moment the elder thief arrived with the cow, the younger thief accosted him, saying—”So you are come safe, brother. Let us go in and divide the money.” To this proposal, the elder thief readily agreed. In the inner yard of the house, the two jars were taken down from the back of the cow; they went to a room, bolted the door, and began dividing. Two mohurs were taken up by the hand, one was put in one place, and the other in another, and they went on doing that till the jars became empty. But last of all one gold mohur remained. The question was—Who was to take it? Both agreed that it should be changed the next morning and the silver cash equally divided. But with whom was the single mohur to remain? There was not a little wrangling about the matter. After a great deal of yea and nay, it was settled that it should remain with the elder thief and that the next morning it should be changed and equally divided.

At night the elder thief said to his wife and the other women of the house, “Look here, ladies, the younger thief will come tomorrow morning to demand the share of the remaining gold mohur; but I don’t mean to give it to him. You do one thing tomorrow. Spread a cloth on the ground in the yard. I will lay myself on the cloth pretending to be dead; and to convince people that I am dead, put a tulasi plant near my head. And when you see the younger thief coming to the door, you set up a loud cry and lamentation. Then he will of course go away, and I shall not have to pay his share of the gold mohur.” To this proposal, the women readily agreed.

Accordingly the next day, at about noon, the elder thief laid himself down in the yard like a corpse with the sacred basil near his head. When the younger thief was seen coming near the house, the women set up a loud cry, and when he came nearer and nearer, wondering what it all meant, they said, “Oh, where did you both go? What did you bring? What did you do to him? Look, he is dead!” So saying they rent the air with their cries.

The younger thief, seeing through the whole, said, “Well, I am sorry my friend and brother are gone. I must now attend his funeral. You all go away from this place, you are but women. I’ll see to it that the remains are well burnt.”

He brought a quantity of straw and twisted it into a rope, which he fastened to the legs of the deceased man, and began tugging him, saying that he was going to take him to the place of burning. While the elder thief was being dragged through the streets, his body was getting dreadfully scratched and bruised, but he held his peace, being resolved to act his part out, and thus escape giving the share of the gold mohur.

The sun had gone down when the younger thief with the corpse reached the place of burning. But as he was making preparations for a funeral pile, he remembered that he had not brought fire with him. If he went for fire leaving the elder thief behind, he would undoubtedly run away. What then was to be done? At last, he tied the straw rope to the branch of a tree and kept the pretended corpse hanging in the air, and he himself climbed into the tree and sat on that branch, keeping tight hold of the rope lest it should break, and the elder thief run away.

While they were in this state, a gang of robbers passed by. On seeing the corpse hanging, the head of the gang said, “This raid of ours has begun very auspiciously. Brahmans and Pandits say that if one starts on a journey one sees a corpse, it is a good omen. Well, we have seen a corpse, it is therefore likely that we shall meet with success this night. If we do, I propose one thing: on our return let us first burn this dead body and then return home.” All the robbers agreed to this proposal. The robbers then entered the house of a rich man in the village, put its inmates to the sword, robbed it of all its treasures, and withal managed it so cleverly that not a mouse stirred in the village.

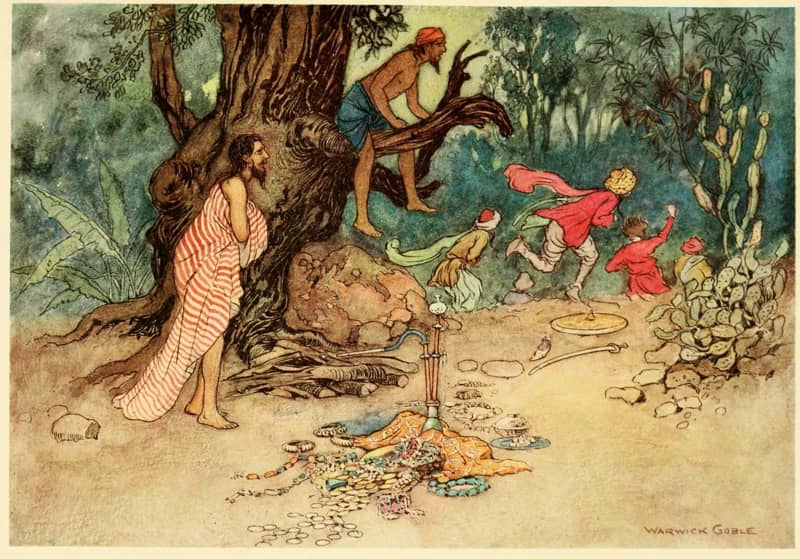

As they were successful beyond measure, they resolved on their return to burn the dead body they had seen. When they came to the place of burning they found the corpse hanging as before, for the elder thief had not yet opened his mouth lest he should be obliged to give half of the gold mohur. The thieves dug a hollow in the ground, brought fuel, and laid it upon the hollow. They took down the corpse from the tree, and laid it upon the pile; and as they were going to set it on fire, the corpse gave out an unearthly scream and jumped up. That very moment the younger thief jumped down from the tree with a similar scream. The robbers were frightened beyond measure. They thought that a Dana (evil spirit) had possessed the corpse and that a ghost jumped down from the tree.

They ran away in great fear, leaving behind them the money and the jewels which they had obtained by robbery. The two thieves laughed heartily, took up all the riches of the robbers, went home, and lived merrily for a long time.