- The Adventures of Two Thieves and of their Son (Folk-tales of Bengal) – I

- The Adventures of Two Thieves and of their Son (Folk-tales of Bengal) – II

The elder thief and the younger thief had one son each. As they had been so far successful in life by practising the art of thieving, they resolved to train their sons in the same profession. There was in the village a Professor of the Science of Roguery, who took pupils and gave them lessons in that difficult science. The two thieves put their sons under this renowned Professor. The son of the elder thief distinguished himself very much and bade fair to surpass his father in the art of stealing.

The lad’s cleverness was tested in the following manner. Not far from the Professor’s house there lived a poor man in a hut, upon the thatch of which climbed a creeper of the gourd kind. In the middle of the thatch, which was also its topmost part, there was a splendid gourd, which the man and his wife watched day and night. They certainly slept at night, but then the thatch was so old and rickety that if even a mouse went up to it bits of straw and particles of earth used to fall inside the hut, and the man and his wife slept right below the spot where the gourd was; so that it was next to impossible to steal the gourd without the knowledge of its owners.

The Professor said to his pupils—for he had many—that anyone who stole the gourd without being caught would be pronounced the dux of the school. Our elder thief’s son at once accepted the offer. He said he would steal away the gourd if he were allowed the use of three things, namely, a string, a cat, and a knife.

The Professor allowed him the use of these three things. Two or three hours after nightfall, the lad, furnished with the three things mentioned above, sat behind the thatch under the eaves, listening to the conversation carried on by the man and his wife lying in bed inside the hut. In a short time, the conversation ceased. The lad then concluded that they must both have fallen asleep. He waited half an hour longer, and hearing no sound inside, gently climbed up on the thatch. Chips of straw and particles of earth fell upon the couple sleeping inside.

The woman woke up, and rousing her husband said, “Look there, someone is stealing the gourd!”

That moment the lad squeezed the throat of the cat, and Puss immediately gave out her usual “Mew! mew! mew!” The husband said, “Don’t you hear the cat mewing? There is no thief; it is only a cat.”

The lad in the meantime cut the gourd from the plant with his knife and tied the string which he had with him to its stalk. But how was he to get down without being discovered and caught, especially as the man and the woman were now awake? The woman was not convinced that it was only a cat; the shaking of the thatch, and the constant falling of bits of straw and particles of dust, made her think that it was a human being that was upon the thatch. She was telling her husband to go out and see whether a man was not there, but he maintained that it was only a cat. While the man and woman were thus disputing with each other, the lad with great force threw down the cat upon the ground, on which the poor animal purred most vociferously; and the man said aloud to his wife, “There it is; you are now convinced that it was only a cat.”

In the meantime, during the confusion created by the clamour of the cat and the loud talk of the man, the lad quietly came down from the thatch with the gourd tied to the string. The next morning the lad produced the gourd before his teacher and described to him and to his admiring comrades the manner in which he had committed the theft. The Professor was in ecstasy, and remarked, “The worthy son of a worthy father.” But the elder thief, the father of our hopeful genius, was by no means satisfied that his son was as yet fit to enter the world. He wanted to prove him still further. Addressing his son he said, “My son, if you can do what I tell you, I’ll think you fit to enter the world. If you can steal the gold chain of the queen of this country from her neck, and bring it to me, I’ll think you fit to enter the world.” The gifted son readily agreed to do the daring deed.

The young thief—for so we shall now call the son of the elder thief—made a reconnaissance of the palace in which the king and queen lived. He reconnoitred all the four gates, and all the outer and inner walls as far as he could; and gathered incidentally a good deal of information, from people living in the neighbourhood, regarding the habits of the king and queen, in what part of the palace they slept, what guards there were near the bed chamber, and who, if any, slept in the antechamber.

Armed with all this knowledge the young thief fixed upon one dark night for doing the daring deed. He took with him a sword, a hammer and some large nails, and put on very dark clothes. Thus accoutred he went prowling about the Lion gate of the palace. Before the zenana could be got at, four doors, including the Lion gate, had to be passed; and each of these doors had a guard of sixteen stalwart men. The same men, however, did not remain all night at their post. As the king had an infinite number of soldiers at his command, the guards at the doors were relieved every hour; so that once every hour at each door there were thirty-two men present, consisting of the relieving party and the relieved. The young thief chose that particular moment of time to enter each of the four doors. At the time of relief when he saw the Lion gate crowded with thirty-two men, he joined the crowd without being taken notice of; he then spent the hour preceding the next relief in the large open space and garden between two doors; and he could not be taken notice of, as the night as well as his clothes was pitch dark. In a similar manner, he passed the second door, the third door, and the fourth door. And now the queen’s bed chamber stared him in the face. It was in the third loft; there was a bright light in it; and a low voice was heard as that of a woman saying something in a humdrum manner. The young thief thought that the voice must be the voice of a maid-servant reciting a story, as he had learnt was the custom in the palace every night, for composing the king and queen to sleep. But how to get up into the third loft? The inner doors were all closed, and there were guards everywhere. But the young thief had with his nails and a hammer: why not drive the nails into the wall and climb up by them? True; but the driving of nails into the wall would make a great noise which would rouse the guards, and possibly the king and queen,—at any rate, the maid-servant reciting stories would give the alarm.

Our erratic genius had considered that matter well before engaging in the work. There is a water clock in the palace that shows the hours, and at the end of every hour a very large Chinese gong is struck, the sound of which is so loud that it is not only all over the palace but over most parts of the city; and the peculiarity of the gong, as of every Chinese gong, was that nearly one minute must elapse after the first stroke before the second stroke could be made, to allow the gong to give out the whole of its sound. The thief fixed upon the minutes when the gong was struck at the end of every hour for driving nails into the wall. At ten o’clock when the gong was struck ten times, the thief found it easy to drive ten nails into the wall. When the gong stopped, the thief also stopped, and either sat or stood quiet on the ninth nail catching hold of the tenth which was above the other. At eleven o’clock he drove into the wall in a similar manner eleven nails, and got a little higher than the second story; and by twelve o’clock he was in the loft where the royal bed chamber was. Peeping in he saw a drowsy maid-servant drowsily reciting a story, and the king and queen apparently asleep. He went stealthily behind the story-telling maid-servant and took his seat. The queen was lying down on a richly furnished bedstead of gold beside the king. The massive chain of gold around the neck of the queen was gleaming in candlelight. The thief quietly listened to the story of the drowsy maidservant. She was becoming more and more sleepy. She stopped for a second, nodded her head, and again resumed the story. It was plain she was under the influence of sleep. In a moment the thief cut off the head of the maid-servant with his sword, and himself went on reciting for some minutes the story which the woman was telling.

The king and queen were unconscious of any change to the person of the storyteller, for they were both in deep sleep. He stripped the murdered woman of her clothes, put them on himself, tied up his own clothes in a bundle, and walking softly, gently took off the chain from the neck of the queen. He then went through the rooms downstairs, and ordered the inner guard to open the door, as she was obliged to go out of the palace for purposes of necessity. The guards, seeing that it was the queen’s maid-servant, readily allowed her to go out. In the same manner, and with the same pretext, he got through the other doors, and at last out into the street. That very night, or rather morning, the young thief put into his father’s hand the gold chain of the queen. The elder thief could scarcely believe his own eyes. It was so like a dream. His joy knew no bounds. Addressing his son he said—”Well done, my son; you are not only as clever as your father, but you have beaten me hollow. The gods give you long life, my son.”

The next morning when the king and queen got up from bed, they were shocked to see the maid-servant lying in a pool of blood. The queen also found that her gold chain was not round her neck. They could not make out how all this could have taken place. How could any thief manage to elude the vigilance of so many guards? How could he get into the queen’s bed chamber? And how could he again escape? The king found from the reports of the guards that a person calling herself the royal maid-servant had gone out of the palace some hours before dawn. All sorts of inquiries were made but in vain. A proclamation was made in the city; a large reward was offered to anyone who would give information tending to the apprehension of the thief and murderer. But no one responded to the call.

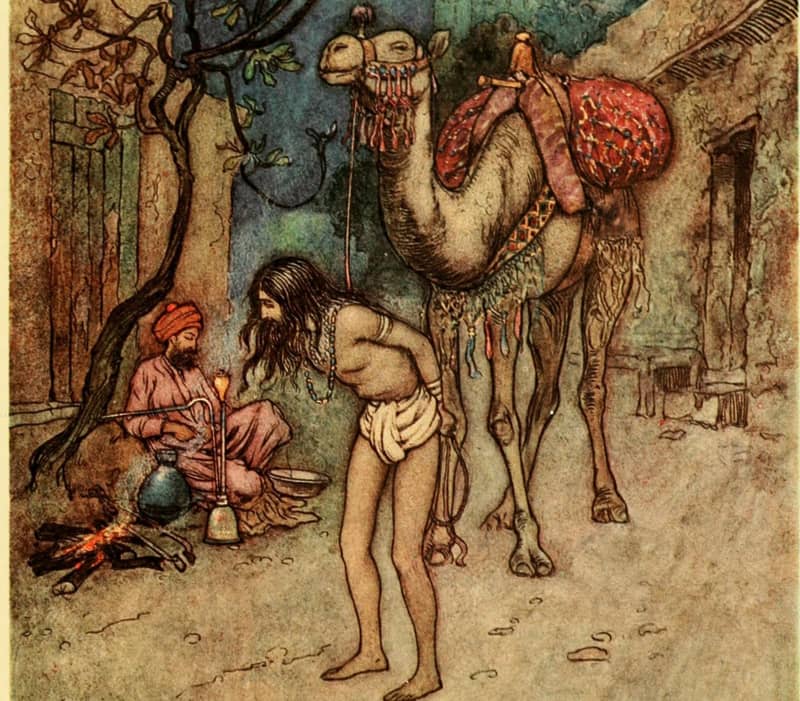

At last, the king ordered a camel to be brought to him. On the back of the animal were placed two large bags filled with gold mohurs. The man taking charge of the bags upon the camel was ordered to go through every part of the city making the following challenge:—”As the thief was daring enough to steal away a gold chain from the neck of the queen, let him further show his daring by stealing the gold mohurs from the back of this camel.” Two days and nights the camel paraded through the city, but nothing happened. On the third night as the camel-driver was going his rounds he was accosted by a sannyasi, who sat on a tiger’s skin before a fire, and near whom was a monstrous pair of tongs. This sannyasi was no other than the young thief in disguise.

The sannyasi said to the camel driver—”Brother, why are you going through the city in this manner? Who is there so daring as to steal from the back of the king’s camel? Come down, friend, and smoke with me.”

The camel driver alighted, tied the camel to a tree on the spot, and began smoking. The mendicant supplied him not only with tobacco but with ganja and other intoxicating drugs so that in a short time the camel driver became quite intoxicated and fell asleep. The young thief led away the camel with the treasure on its back in the dead of night, through narrow lanes and bye-paths to his own house. That very night the camel was killed, and its carcass buried in deep pits in the earth, and the thing was so managed that no one could discover any trace of it.

The next morning when the king heard that the camel-driver was lying drunk in the street and that the camel had been made away with together with the treasure, he was almost beside himself with anger. A proclamation was made in the city to the effect that whoever caught the thief would get the reward of a lakh of rupees.

The son of the younger thief—who, by the way, was in the same school of roguery with the son of the elder thief, though he did not distinguish himself so much—now came to the front and said that he would apprehend the thief. He of course suspected that the son of the elder thief must have done it—for who so daring and clever as he? In the evening of the following day the son of the younger thief disguised himself as a woman, and coming to that part of the town where the young thief lived, began to weep very much, and went from door to door saying—”O sirs, can any of you give me a bit of camel’s flesh, for my son is dying, and the doctors say nothing but eating camel’s meat can save his life. O for pity’s sake, do give me a bit of camel’s flesh.” At last, he went to the house of the young thief and begged of the wife—for the young thief himself was out—to tell him where he could get hold of camel’s flesh, as his son would assuredly perish if it could not be got. Saying this he rents the air with his cries and falls down at the feet of the young thief’s wife.

Woman as she was, though the wife of a thief, she felt pity for the supposed woman, and said—”Wait, and I will try and get some camel’s flesh for your son.” So, she secretly went to the spot where the dead camel had been buried, brought a small quantity of flesh, and gave it to the party.

The son of the younger thief was now entranced with joy. He went and told the king that he had succeeded in tracing the thief, and would be ready to deliver him up at night if the king would send some constables with him. At night the elder thief and his son were captured, the body of the camel dug out, and all the treasures in the house seized.

The following morning the king sat in judgment. The son of the elder thief confessed that he had stolen the queen’s gold chain, killed the maid-servant, and taken away the camel; but he added that the person who had detected him and his father—the younger thief—were also thieves and murderers, of which fact he gave undoubted proofs. As the king had promised to give a lakh of rupees to the detective, that sum was placed before the son of the younger thief. But soon after he ordered four pits to be dug in the earth in which were buried alive, with all sorts of thorns and thistles, the elder thief and the younger thief, and their two sons.

Here my story endeth,

The Natiya-thorn withereth, etc.