- The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead – Part I

- The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead – Part II

There was a certain king who had six queens, none of whom bore children. Physicians, holy sages, and mendicants, were consulted, and countless drugs were had recourse to, but all to no purpose. The king was disconsolate. His ministers told him to marry a seventh wife, and he was accordingly on the lookout.

In the royal city, there lived a poor old woman who used to pick up cow dung from the fields, make it into cakes, dry them in the sun, and sell them in the market for fuel. This was her only means of subsistence. This old woman had an daughter exquisitely beautiful. Her beauty excited the admiration of everyone who saw her; and it was solely in consequence of her surpassing beauty that three young ladies, far above her in rank and station, contracted friendship with her. Those three young ladies were the daughter of the king’s minister, the daughter of a wealthy merchant, and the daughter of the royal priest. These three young ladies, together with the daughter of the poor old woman, were one day bathing in a tank not far from the palace. As they were performing their ablutions, each dwelt on her own good qualities. “Look here, sister,” said the minister’s daughter, addressing the merchant’s daughter, “the man that marries me will be a happy man, for he will not have to buy clothes for me. The cloth which I once put on never gets soiled, never gets old, never tears.” The merchant’s daughter said, “And my husband too will be a happy man, for the fuel which I use in cooking never gets turned into ashes. The same fuel serves from day to day, from year to year.” “And my husband will also become a happy man,” said the daughter of the royal chaplain, “for the rice which I cook one day never gets finished, and when we have all eaten, the same quantity which was first cooked remains always in the pot.” The daughter of the poor old woman said in her turn, “And the man that marries me will also be happy, for I shall give birth to twin children, a son and a daughter. The daughter will be divinely fair, and the son will have the moon on his forehead and stars on the palms of his hands.”

The above conversation was overheard by the king, who, as he was on the lookout for a seventh queen, used to skulk about in places where women met together. The king thus thought in his mind—”I don’t care a straw for the girl whose clothes never tear and never get old; neither do I care for the other girl whose fuel is never consumed; nor for the third girl whose rice never fails in the pot. But the fourth girl is quite charming! She will give birth to twin children, a son and a daughter; the daughter will be divinely fair, and the son will have the moon on his forehead and stars on the palms of his hands. That is the girl I want. I’ll make her my wife.”

On making inquiries on the same day, the king found that the fourth girl was the daughter of a poor old woman who picked up cow dung from the fields; but though there was thus an infinite disparity in rank, he determined to marry her. On the very same day, he sent for the poor old woman. She, poor thing, was quite frightened when she saw a messenger of the king standing at the door of her hut. She thought that the king had sent for her to punish her, because, perhaps, she had someday unwittingly picked up the dung of the king’s cattle. She went to the palace and was admitted into the king’s private chamber. The king asked her whether she had a very fair daughter and whether that daughter was the friend of his own minister’s and priest’s daughters. When the woman answered in the affirmative, he said to her, “I will marry your daughter, and make her my queen.” The woman hardly believed her own ears—the thing was so strange. He, however, solemnly declared to her that he had made up his mind, and was determined to marry her daughter. It was soon known in the capital that the king was going to marry the daughter of the old woman who picked up cow dung in the fields. When the six queens heard the news, they would not believe it, till the king himself told them that the news was true. They thought that the king had somehow got mad. They reasoned with him thus—”What folly, what madness, to marry a girl who is not fit to be our maid-servant! And you expect us to treat her as our equal—a girl whose mother goes about picking up cow dung in the fields! Surely, my lord, you are beside yourself!” The king’s purpose, however, remained unshaken. The royal astrologer was called, and an auspicious day was fixed for the celebration of the king’s marriage. On the appointed day the royal priest tied the marital knot, and the daughter of the poor old picker-up of cow dung in the fields became the seventh and best-beloved queen.

Sometime after the celebration of the marriage, the king went for six months to another part of his dominions. Before setting out he called to him the seventh queen, and said to her, “I am going away to another part of my dominions for six months. Before the expiration of that period, I expect you to be confined. But I should like to be present with you at the time, as your enemies may do mischief. Take this golden bell and hang it in your room. When the pains of childbirth come upon you, ring this bell, and I will be with you in a moment in whatever part of my dominions I may be at the time. Remember, you are to ring the bell only when you feel the pains of childbirth.” After saying this the king started on his journey. The six queens, who had overheard the king, went on the next day to the apartments of the seventh queen, and said, “What a nice bell of gold you have got, sister! Where did you get it, and why have you hung it up?” The seventh queen, in her simplicity, said, “The king has given it to me, and if I were to ring it, the king would immediately come to me wherever he might be at the time.” “Impossible!” said the six queens, “you must have misunderstood the king. Who can believe that this bell can be heard at a distance of hundreds of miles? Besides, if it could be heard, how would the king be able to travel a great distance in the twinkling of an eye? This must be a hoax. If you ring the bell, you will find that what the king said was pure nonsense.” The six queens then told her to make a trial. At first, she was unwilling, remembering what the king had told her; but at last, she was prevailed upon to ring the bell. The king was at the moment halfway to the capital of his other dominions, but at the ringing of the bell, he stopped short in his journey, turned back, and in no time stood in the queen’s apartments. Finding the queen going about in her rooms, he asked why she had rung the bell though her hour had not come. She, without informing the king of the entreaty of the six queens, replied that she rang the bell only to see whether what he had said was true. The king was somewhat indignant, told her distinctly not to ring the bell again till the moment of the coming upon her of the pains of childbirth, and then went away. After the lapse of some weeks, the six queens again begged of the seventh queen to make a second trial of the bell. They said to her, “The first time when you rang the bell, the king was only at a short distance from you, it was therefore easy for him to hear the bell and to come to you; but now he has long ago settled in his other capital, let us see if he will now hear the bell and come to you.” She resisted for a long time, but was at last prevailed upon by them to ring the bell. When the sound of the bell reached the king he was in court dispensing justice, but when he heard the sound of the bell (and no one else heard it) he closed the court and in no time stood in the queen’s apartments. Finding that the queen was not about to be confined, he asked her why she had again rung the bell before her hour. She, without saying anything of the importance of the six queens, replied that she merely made a second trial of the bell. The king became very angry, and said to her, “Now listen, since you have called me twice for nothing, let it be known to you that when the throes of childbirth do really come upon you, and you ring the bell ever so lustily, I will not come to you. You must be left to your fate.” The king then went away.

At last, the day of the seventh queen’s deliverance arrived. On first feeling the pain, she rang the golden bell. She waited, but the king did not make his appearance. She rang again with all her might, but still, the king did not make his appearance. The king certainly did hear the sound of the bell, but he did not come as he was displeased with the queen. When the six queens saw that the king did not come, they went to the seventh queen and told her that it was not customary with the ladies of the palace to be confined in the king’s apartments; she must go to a hut near the stables. They then sent for the midwife of the palace and heavily bribed her to make away with the infant the moment it should be born into the world. The seventh queen gave birth to a son who had the moon on his forehead and stars on the palms of his hands, and also to an uncommonly beautiful girl. The midwife had come and provided with a couple of newly born pups. She put the pups before the mother, saying—”You have given birth to these,” and took away the twin children in an earthen vessel. The queen was quite insensible at the time and did not notice the twins at the time they were carried away. The king, though he was angry with the seventh queen, yet remembering that she was destined to give birth to the heir of his throne, changed his mind, and came to see her the next morning. The pups were produced before the king as the offspring of the queen. The king’s anger and vexation knew no bounds. He ordered that the seventh queen should be expelled from the palace, that she should be clothed in leather, and that she should be employed in the marketplace to drive away crows and to keep off dogs. Though scarcely able to move she was driven away from the palace, stripped of her fine robes, clothed in leather, and set to drive away the crows of the marketplace.

The midwife, when she put the twins in the earthen vessel, thought of the best way to destroy them. She did not think it proper to throw them into a tank, lest they should be discovered the next day. Neither did she think of burying them in the ground, lest they should be dug up by a jackal and exposed to the gaze of people. The best way to make an end of them, she thought, would be to burn them, and reduce them to ashes, so that no trace might be left of them. But how could she, at that dead hour of night, burn them without some other person helping her? A happy thought struck her. There was a potter on the outskirts of the city, who used during the day to mould vessels of clay on his wheel and burn them during the latter part of the night. The midwife thought that the best plan would be to put the vessel with the twins along with the unburnt clay vessels which the potter had arranged in order and go to sleep expecting to get up late at night and set them on fire; in this way, she thought, the twins would be reduced to ashes. She, accordingly, put the vessel with the twins along with the unburnt clay vessels of the potter and went away.

Somehow or other, that night the potter and his wife overslept themselves. It was near the break of day when the potter’s wife, awaking out of sleep, roused her husband, and said, “Oh, my good man, we have overslept ourselves; it is now near morning and I much fear it is now too late to set the pots on fire.” Hastily unbolting the door of her cottage, she rushed out to the place where the pots were ranged in rows. She could scarcely believe her eyes when she saw that all the pots had been baked and were looking bright red, though neither she nor her husband had applied any fire to them. Wondering at her good luck, and not knowing what to make of it, she ran to her husband and said, “Just come and see!” The potter came, saw, and wondered. The pots had never before been so well baked. Who could have done this? This could have proceeded only from some god or goddess. Fumbling about the pots, he accidentally upturned one in which, lo and behold, were seen huddled up together two newly born infants of unearthly beauty. The potter said to his wife, “My dear, you must pretend to have given birth to these beautiful children.” Accordingly, all arrangements were made, and in due time it was given out that the twins had been born to her. And such lovely twins they were! On the same day, many women of the neighbourhood came to see the potter’s wife and the twins to whom she had given birth and to offer their congratulations on this unexpected good fortune. As for the potter’s wife, she could not be too proud of her pretended children, and said to her admiring friends, “I had hardly hoped to have children at all. But now that the gods have given me these twins, may they receive the blessings of you all, and live forever!”

The twins grew and were strengthened. The brother and sister, when they played about in the fields and lanes, were the admiration of everyone who saw them; and all wondered at the uncommonly good luck of the potter in being blessed with such angelic children. They were about twelve years old when the potter, their reputed father, became dangerously ill. It was evident to all that his sickness would end in death. The potter, perceiving his last end approaching, said to his wife, “My dear, I am going the way of all the earth; but I am leaving to you enough to live upon; live on and take care of these children.” The woman said to her husband, “I am not going to survive you. Like all good and faithful wives, I am determined to die along with you. You and I will burn together on the same funeral pyre. As for the children, they are old enough to take care of themselves, and you are leaving them enough money.” Her friends tried to dissuade her from her purpose but in vain. The potter died; and as his remains were being burnt, his wife, now a widow, threw herself on the pyre, and burnt herself to death.

The boy with the moon on his forehead—by the way, he always kept his head covered with a turban lest the halo should attract notice—and his sister, now broke up the potter’s establishment, sold the wheel and the pots and pans, and went to the bazaar in the king’s city. The moment they entered, the bazaar was lit up on a sudden. The shopkeepers of the bazaar were greatly surprised.

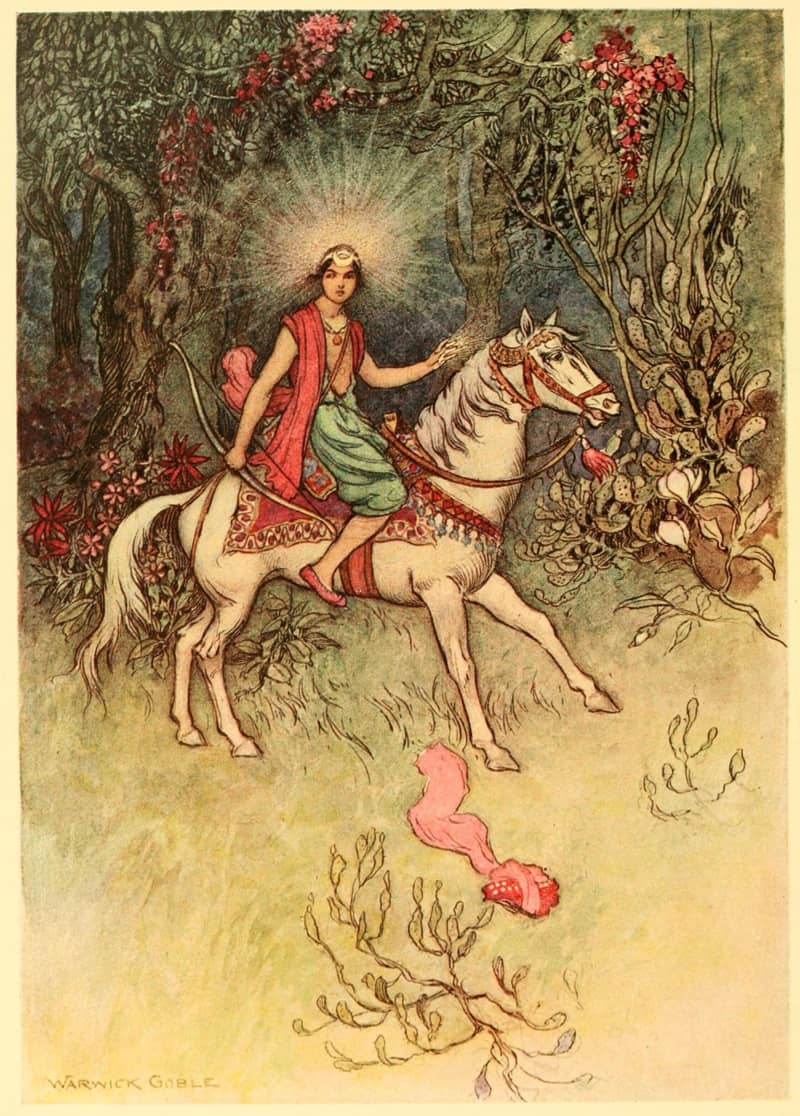

They thought some divine beings must have entered the place. They looked upon the beautiful boy and his sister with wonder. They begged them to stay in the bazaar. They built a house for them. When they used to ramble about, they were always followed at a distance by the woman clothed in leather, who was appointed by the king to drive away the crows of the bazaar. By some unaccountable impulse, she used also to hang about the house in which they lived. The boy in a short time bought a horse and went a-hunting in the neighbouring forests. One day while he was hunting, the king was also hunting in the same forest, and seeing a brother huntsman the king drew near to him. The king was struck with the beauty of the lad and a yearning for him the moment he saw him. As a deer went past, the youth shot an arrow, and the reaction of the force necessary to shoot the arrow made the turban of his head fall off, on which a bright light, like that of the moon, was seen shining on his forehead.

Continued..