- The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead – Part I

- The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead – Part II

The king saw and immediately thought of the son with the moon on his forehead and stars on the palms of his hands who was to have been born of his seventh queen. The youth on letting fly the arrow galloped off, in spite of the earnest entreaty of the king to wait and speak to him. The king went home a sadder man than he came out of it. He became very moody and melancholy. The six queens asked him why he was looking so sad. He told them that he had seen in the woods a lad with the moon on his forehead, which reminded him of the son who was to be born of the seventh queen.

The six queens tried to comfort him in the best way they could, but they wondered who the youth could be. Was it possible that the twins were living? Did not the midwife say that she had burnt both the son and the daughter to ashes? Who, then, could this lad be? The midwife was sent for by the six queens and questioned. She swore that she had seen the twins burnt. As for the lad whom the king had met with, she would soon find out who he was.

On making inquiries, the midwife soon found out that two strangers were living in the bazaar in a house that the shopkeepers had built for them. She entered the house and saw the girl only, as the lad had again gone out a-shooting. She pretended to be their aunt, who had gone away to another part of the country shortly after their birth; she had been searching after them for a long time and was now glad to find them in the king’s city near the palace.

She greatly admired the beauty of the girl, and said to her, “My dear child, you are so beautiful, you require the kataki (Calotropis gigantea) flower properly to set off your beauty. You should tell your brother to plant a row of that flower in this courtyard.”

“What flower is that, auntie? I never saw it.”

“How could you have seen it, my child? It is not found here; it grows on the other side of the ocean, guarded by seven hundred Rakshasas.”

“How, then,” said the girl, “will my brother get it?”

“He may try to get it, if you speak, to him,” replied the woman. The woman made this proposal in the hope that the boy with the moon on his forehead would perish in an attempt to get the flower.

When the youth with the moon on his forehead returned from hunting, his sister told him of the visit paid to her by their aunt, and requested him, if possible, to get for her the kataki flower. He was sceptical about the existence of any aunt of theirs in the world, but he was resolved that to please his beloved sister, he would get the flower on which she had set her heart.

The next morning, accordingly, he started on his journey, after bidding his sister not to stir out of the house till his return. He rode on his fleet steed, which was of the pakshiraj (the king of birds) tribe, and soon reached the outskirts of what seemed to him dense forests of interminable length.

He described some Rakshasas prowling about. He went to some distance, shot with his arrows some deer and rhinoceroses in the neighbouring thickets, and, approaching the place where the Rakshasas were prowling about, called out, “O auntie dear, O auntie dear, your nephew is here.”

A huge Rakshasi came towards him and said, “O, you are the youth with the moon on your forehead and stars on the palms of your hands. We were all expecting you, but as you have called me aunt, I will not eat you up. What is it you want? Have you brought any eatables for me?”

The youth gave her the deer and rhinoceroses which he had killed. Her mouth watered at the sight of the dead animals, and she began eating them. After swallowing down all the carcasses, she said, “Well, what do you want?”

The youth said, “I want some kataki flowers for my sister.”

She then told him that it would be difficult for him to get the flower, as it was guarded by seven hundred Rakshasas; however, he might make the attempt, but in the first instance he must go to his uncle on the north side of that forest.

While the youth was going to his uncle of the north, on the way he killed some deer and rhinoceroses, and seeing a gigantic Rakshasa at some distance, cried out, “Uncle dear, uncle dear, your nephew is here. Auntie has sent me to you.”

The Rakshasa came near and said, “You are the youth with the moon on your forehead and stars on the palms of your hands; I would have swallowed you outright, had you not called me uncle, and had you not said that your aunt had sent you to me. Now, what is it you want?”

The savoury deer and rhinoceroses were then presented to him; he ate them all and then listened to the petition of the youth. The youth wanted the kataki flower.

The Rakshasa said, “You want the kataki flower! Very well, try and get it if you can. After passing through this forest, you will come to an impenetrable forest of kachiri. You will say to that forest, ‘O mother kachiri! Please make way for me, or else I die.’ On that, the forest will open up a passage for you. You will next come to the ocean. You will say to the ocean, ‘O mother ocean! please make way for me, or else I die,’ and the ocean will make way for you. After crossing the ocean, you enter the gardens where the kataki blooms. Good-bye; do as I have told you.”

The youth thanked his Rakshasa uncle and went on his way. After he had passed through the forest, he saw before him an impenetrable forest of kachiri. It was so close and thick, and withal so bristling with thorns, that not a mouse could go through it. Remembering the advice of his uncle, he stood before the forest with folded hands, and said, “O mother kachiri! Please make way for me, or else I die.” On a sudden, a clean path was opened up in the forest, and the youth gladly passed through it. The ocean now lay before him. He said to the ocean, “O mother ocean! make way for me, or else I die.” Forthwith the waters of the ocean stood up on two sides like two walls, leaving an open passage between them, and the youth passed through dryshod.

Now, right before him were the gardens of the kataki flower. He entered the inclosure and found himself in a spacious palace which seemed to be unoccupied. On going from apartment to apartment he found a young lady of more than earthly beauty sleeping on a bedstead of gold. He went near, and noticed two little sticks, one of gold and the other of silver, lying in the bedstead. The silver stick lay near the feet of the sleeping beauty, and the golden one near the head. He took up the sticks in his hands, and as he was examining them, the golden stick accidentally fell upon the feet of the lady.

In a moment the lady woke and sat up, and said to the youth, “Stranger, how have you come to this dismal place? I know who you are, and I know your history. You are the youth with the moon on your forehead and stars on the palms of your hands. Flee, flee from this place! This is the residence of seven hundred Rakshasas who guard the gardens of the kataki flower. They have all gone a-hunting; they will return by sundown; and if they find you here you will be eaten up. One Rakshasi brought me from the earth where my father is king. She loves me very dearly, and will not let me go away. By means of these gold and silver sticks, she kills me when she goes away in the morning, and by means of those sticks, she revives me when she returns in the evening. Flee, flee hence, or you die!” The youth told the young lady how his sister wished very much to have the kataki flower, how he passed through the forest of kachiri, and how he crossed the ocean. He said also that he was determined not to go alone, he must take the young lady along with him. The remaining part of the day they spent together in rambling about the gardens. As the time was drawing near when the Rakshasas should return, the youth buried himself amid an enormous heap of kataki flowers which lay in an adjoining apartment, after killing the young lady by touching her head with the golden stick. Just after sunset, the youth heard the sound of a mighty tempest: it was the return of the seven hundred Rakshasas into the gardens.

One of them entered the apartment of the young lady, revived her, and said, “I smell a human being, I smell a human being.”

The young lady replied, “How can a human being come to this place? I am the only human being here.”

The Rakshasi then stretched herself on the floor and told the young lady to shampoo her legs. As she was going on shampooing, she let a teardrop on the Rakshasi’s leg. “Why are you weeping, my dear child?” asked the raw eater; “Why are you weeping? Is anything troubling you?”

“No, mamma,” answered the young lady, “nothing is troubling me. What can trouble me, when you have made me so comfortable? I was only thinking what will become of me when you die.”

“When I die, child?” said the Rakshasi; “shall I die? Yes, of course, all creatures die; but the death of a Rakshasa or Rakshasi will never happen. You know, child, that deep tank in the middle part of these gardens. Well, at the bottom of that tank, there is a wooden box, in which there are a male and a female bee. It is ordained by fate that if a human being who has the moon on his forehead and stars on the palms of his hands were to come here and dive into that tank, get hold of the same wooden box, and crush to death the male and female bees without letting a drop of their blood fall to the ground, then we should die. But the accomplishment of this decree of fate is, I think, impossible. For, in the first place, there can be no such human being who will have the moon on his forehead and stars on the palms of his hands; and, in the second place, if there be such a man, he will find it impossible to come to this place, guarded as it is by seven hundred of us, encompassed by a deep ocean, and barricaded by an impervious forest of kachiri—not to speak of the outposts and sentinels that are stationed on the other side of the forest. And then, even if he succeeds in coming here, he will perhaps not know the secret of the wooden box; and even if he knows of the secret of the wooden box, he may not succeed in killing the bees without letting a drop of their blood fall on the ground. And woe be to him if a drop does fall on the ground, for in that case he will be torn up into seven hundred pieces by us. You see then, child, that we are almost immortal—not actually, but virtually so. You may, therefore, dismiss your fears.”

On the next morning, the Rakshasi got up, killed the young lady by means of the sticks, and went away in search of food along with other Rakshasas and Rakshasis. The lad, who had the moon on his forehead and stars on the palms of his hands, came out of the heap of flowers and revived the young lady. The young lady recited to the young man the whole of the conversation she had had with the Rakshasi.

It was a perfect revelation to him. He, however, lost no time in beginning to act. He shut the heavy gates of the gardens. He dived into the tank and brought up the wooden box. He opened the wooden box and caught hold of the male and female bees as they were about to escape. He crushed them on the palms of his hands, besmearing his body with every drop of their blood. The moment this was done, loud cries and groans were heard around about the inclosure of the gardens.

Agreeably to the decree of fate, all the Rakshasas approached the gardens and fell down dead. The youth with the moon on his forehead took as many kataki flowers as he could, together with their seeds, and left the palace, around which were lying in mountain heaps the carcases of the mighty dead, in company with the young and beautiful lady. The waters of the ocean retreated before the youth as before, and the forest of kachiri also opened up a passage through it; The happy couple reached the house in the bazaar, where they were welcomed by the sister of the youth who had the moon on his forehead.

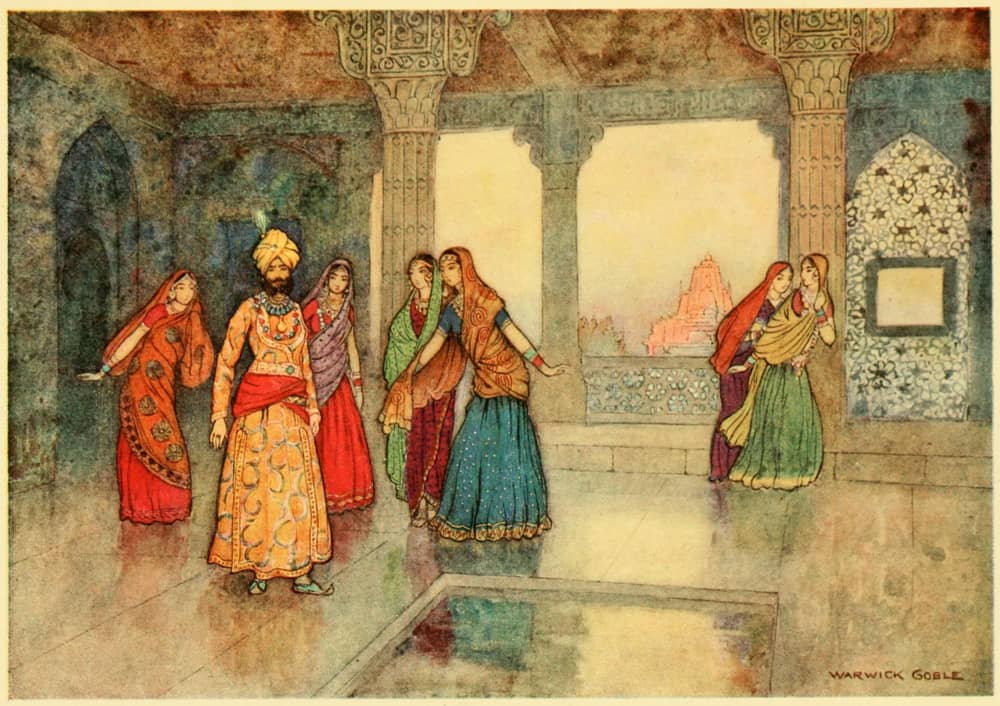

On the following morning the youth, as usual, went to hunt. The king was also there. A deer passed by, and the youth shot an arrow. As he shot, the turban as usual fell off his head, and a bright light issued from it. The king saw and wondered. He told the youth to stop, as he wished to contract friendship with him. The youth told him to come to his house and gave him his address. The king went to the house of the youth in the middle of the day. Pushpavati—for that was the name of the young lady that had been brought from beyond the ocean—told the king—for she knew the whole history—how his seventh queen had been persuaded by the other six queens to ring the bell twice before her time, how she was delivered of a beautiful boy and girl, how pups were substituted in their room, how the twins were saved in a miraculous manner in the house of the potter, how they were well treated in the bazaar, and how the youth with the moon on his forehead rescued her from the clutches of the Rakshasas. The king mightily incensed with the six queens, and had them, on the following day, buried alive in the ground. The seventh queen was then brought from the marketplace and reinstated in her position; and the youth with the moon on his forehead, and the lovely Pushpavati and their sister, lived happily together.

Here my story endeth,

The Natiya-thorn withereth, etc.