ALABORING man named Abdul Karim, with his wife, Zeeba—”the beautiful one”—lived in a sheltered valley, surrounded by hills, the sides of which were covered with fine gardens, in which the peach, the grape, the mulberry, and other delicious fruits grew in great profusion.

Although his wife’s name was Zeeba she was very plain in appearance. But from having been named Zeeba, she thought she was beautiful, and thus it came about that, moved by vanity, her two children were named, the boy, Yusuf, or Joseph, who as you know, was sold by his brethren into Egypt and became next to the King; and the girl, Fatima, after Fatima, the favourite daughter of Mahomet, and the wife of the famous Ali.

Now Abdul Karim was only a labourer on the land, receiving no wages, merely being paid in grain and cloth sufficient for the wants of himself and his family. Of money, he knew nothing except by name.

One day his master was so pleased with his work that he gave him ten “krans,” equivalent to about a dollar of our money. To Abdul Karim, this seemed great wealth, and directly his day’s work was done, he ran home to his wife and said: “Look, Zeeba, there are riches for you!” and spread out the money before her. His good wife was delighted, and so were the children.

Then Abdul Karim said: “How shall we spend this great sum? The master has also given me a day’s holiday, so if you don’t mind, I will go to the famous city of Meshed, which is only twenty miles from here, and after placing two krans on the shrine of the holy Imam, I will then visit the bazaars and buy everything you and the children desire.”

“You would better buy me a piece of silk for a new dress,” said Zeeba.

“I want a fine horse and a sword,” said little Yusuf.

“I would like an Indian handkerchief and a pair of gold slippers,” said Fatima.

“They shall be here by tomorrow night,” said the father, and taking a big stick, he set off on his journey.

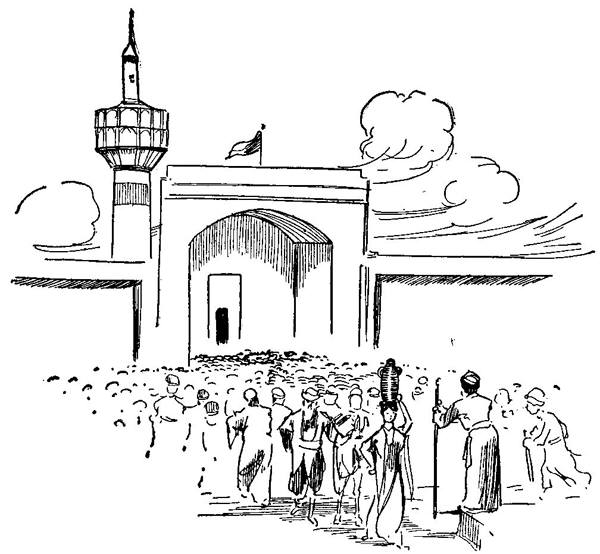

Then coming to the gate of the shrine, he asked an old priest if he might enter. “Yes, my son,” was the reply. “Go in and give what thou canst spare to the mosque, and Allah will reward thee.”

So Abdul Karim walked through the great court, amidst worshipers from every city in Asia. With open-mouthed astonishment he gazed at the riches of the temple, the jewels, the lovely carpets, the silks, the golden ornaments, and with humility he placed his two pieces of money on the sacred tomb. Then through the noise and bustle of the crowded streets, he went until he found the bazaars.

He found the sellers of fruits in one place, in another those who sold pots and pans, then he came to the jewellers, the bakers, the butchers, each trade having its part of the bazaar, and so on until he reached that part where there were only those who sold silks.

He entered one of the shops and asked to see some silks, and after much picking and choosing, fixed upon a superb piece of purple silk with an embroidered border of exquisite design. “I will take this,” he said. “What is the price?”

“I shall only ask you two hundred krans, as you are a new customer,” said the shopkeeper. “Anybody else but you would have to pay three or four hundred.”

“Two hundred krans,” repeated Abdul Karim, in astonishment. “Surely you have made a mistake. Do you mean krans like these?” taking one out of his pocket.

“Certainly I do,” replied the shopkeeper, “and let me tell you it is very cheap at that price.”

Abdul Karim pictured the disappointment of his wife. “Poor Zeeba,” he sighed.

“Poor who?” said the silk merchant.

“My wife,” said Abdul Karim.

“I will tell you about it,” said Abdul Karim. “Because I did my work well, my master gave me ten krans, the first time I ever had any money. After giving two krans to the shrine, I intended to buy a piece of silk for my wife, a horse and sword for my little boy Yusuf, and an Indian handkerchief and a pair of gold slippers for my little girl Fatima. And here you ask me two hundred krans for one piece of silk. How can I pay you and buy the other things?”

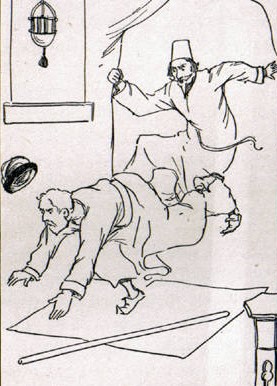

“Here I have been wasting my time and rumpling my beautiful silks for a fool like you,” cried the angry merchant. “Get out of my shop! Go home to your stupid Zeeba and your stupid children. Buy them some stale cakes and some black sugar, and don’t put your head in my shop again, or it will be worse for you.”

Then he took off his slipper, and with many blows drove poor Abdul Karim out into the street.

Then Abdul Karim went to the horse market, only to find that the lowest-priced horse would cost two hundred and fifty krans.

The horse dealer mocked him when they found he had only eight krans, and suggested that he buy the sixteenth part of a donkey for his little son. As for a sword, he found that it would cost at least thirty krans; while a pair of golden slippers would run into many hundreds of krans; and for an Indian handkerchief, the price was twelve krans.

As poor Abdul Karim bent his weary way home, he met a beggar crying: “Dear friend, give me something, for tomorrow is Friday”—the Mahommedan Sunday. “He that giveth to the poor, lendeth to the Lord, and of a certainty the Lord will pay him back a hundredfold.”

“Of all the men I have met today, you are the only one with whom I can deal,” said simple Abdul Karim. “Here are eight krans. Use them in the service of God, and don’t forget to pay me back a hundredfold.”

Wrapping up the eight krans very carefully, the cunning beggar promised someday to return them a hundredfold.

At last Abdul Karim came in sight of his cottage, and little Yusuf, who had been all day on the lookout for him, ran breathlessly to meet him. “Where’s my horse and sword, Father?” he cried. And Fatima, who had just come up, called out, “And my handkerchief and golden slippers?” And Zeeba asked for her bit of silk.

Poor Abdul Karim looked so confused, that his wife said: “Be quiet, my dears. Your father could not bring them all with him, so he has packed them on Yusuf’s horse and left him in charge of a servant, who will be here presently.” But when she heard his story, and above all that he had given eight krans to a beggar, she got very angry and marched off and told the master.

But the master was still more angry, and said: “What! the blockhead gave his eight krans to a beggar? Send him to me.” And when Abdul Karim came before him, he said scornfully: “You must fancy yourself a big man, Abdul. I never give more than a copper coin to a beggar, but Your Excellency gives them silver. The beggar promised that you should be repaid a hundredfold, did he? And it shall be so, even now.” Then as Abdul’s face brightened, he laughed and said: “Not in money, but in stripes.” And his servants threw Abdul on the ground and gave him one hundred blows on his bare feet.

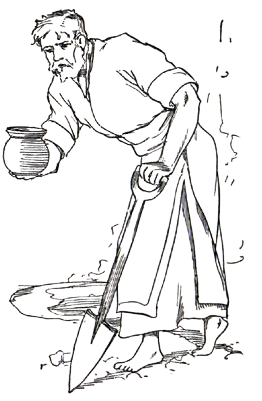

So for many days, Abdul laboured under the scorching sun, until he had dug down to a depth of about thirty feet, and then he came upon a brass vessel, finely chased, full of round white stones, which fairly dazzled his eyes in the fierce sunlight. He put one in his mouth and tried to break it with his teeth, but could not.

Then he said to himself, “The master has planted some rice and it has turned into stones. Perhaps there are some more.” And going down a few feet lower, he found another pot filled with sparkling stones of various colours.

Then he remembered that he had seen pretty pieces of glass like these for sale in Meshed, and made up his mind that on the first opportunity, he would again visit the city and take the stones with him. Meanwhile, he would hide them, and say nothing.

Abdul did not have to wait long for a holiday, for on finding water a little lower down, his master was so pleased that he gave him a well-deserved rest, and then Abdul set off for Meshed. But before entering the city, he hid most of the treasure at the foot of a tree under a big stone. Then with still a pocket full, he went straight to the shop where he had seen such stones and spoke to the shopkeeper who was seated at the entrance to his shop, calmly smoking his water pipe.

“Do you want to buy any more stones like those?” he asked, pointing to some in a brass tray. “Yes, have you got one?” replied the merchant, for Abdul did not look like a man who was likely to have more than one, if any.

“I have a pocket full of them,” said Abdul.

“You have a pocket full of pebbles, more likely,” said the jeweller. But when Abdul took out a handful and showed him, he was so astonished that he could hardly speak. Trembling in every limb, he bade Abdul wait a minute, and leaving his apprentice in charge, he hastily left the shop. When he returned, the chief of the police was with him.

“I am innocent,” cried the jeweller. “There is the man. His pockets are filled with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and pearls of great price. Without doubt, he has found the long-lost treasure of Cyrus.”

Then Abdul was searched; the precious stones were found upon him; and when they had brought Zeeba and the children, the whole family were sent under a guard of five hundred soldiers to the capital.

While all these things were taking place, the King saw in his dreams, for three nights, one after the other, the Holy Prophet, who, looking steadfastly at him, exclaimed: “Abbas, protect and favour my friend.” And on the third night, the King took courage and said to the Prophet: “And who is thy friend?” And the answer came:

“He is a poor labouring man, Abdul Karim by name, who of his poverty gave one-fifth to the shrine at Meshed, and now, because he has found the King’s treasure, they have bound him, and are bringing him to this city to oppress him.”

So the King went forth on two days journey to meet Abdul. First came one hundred horsemen. Next, poor Abdul, seated on a camel, with his arms bound tightly. Walking behind the camel were the weeping children and their mother. Then came the foot soldiers guarding the treasure. The King made the camel kneel, and with his own hands undid the cruel bonds.

Then with tears running down his face, Abdul knelt before the King and pleaded for his dear ones, saying: “If thou slay me, at least let these innocent ones go free!”

Lifting Abdul from the ground, the King then said: “I am come to honour, not to slay thee. When thou hast rested, thou shalt return to thine own province, not as a prisoner, but as the Governor thereof.” And smiling, he added:

“Already is the silk dress prepared for Zeeba; the horse and sword for Yusuf; and the Indian handkerchief and the golden slippers for Fatima have not been forgotten.” For the King had read in the report of the chief of police all the details of Abdul’s case.

And so it was that Abdul’s piety and gift to the shrine had come back, not a hundredfold, but beyond his wildest dreams, and the shrine and the poor benefited greatly thereby.