- The Little Mermaid (Original) – Part I

- The Little Mermaid (Original) – Part II

- The Little Mermaid (Original) – Part III

- The Little Mermaid (Original) – Part IV

At length, she could resist no longer and opened her heart to one of her sisters, from whom all the others immediately learned her secret, though they told it to no one else, except to a couple of other mermaids, who divulged it to nobody, except to their most intimate friends. One of these happened to know who the prince was. She, too, had seen the gala on ship-board and informed them whence he came, and where his kingdom lay.

“Come, little sister,” said the other princesses; and, entwining their arms, they rose up in a long row out of the sea at the spot where they knew the prince’s palace stood.

This was built of bright yellow, shining stone, with a broad flight of marble steps, the last of which reached down into the sea. Magnificent golden cupolas rose above the roof, and marble statues, closely imitating life, were placed between the pillars that surrounded the edifice. One could see, through the transparent panes of the large windows, right into the magnificent rooms, fitted with costly silk curtains and splendid hangings, and ornamented with large pictures on all the walls; so that it was a pleasure to look at them. In the middle of the principal room, a large fountain threw up its sparkling jets as high as the glass cupola in the ceiling, through which the sun shone down upon the water, and on the beautiful plants growing in the wide basin that contained it.

Now that she knew where he lived, she spent many an evening, and many a night, on the neighbouring water. She swam much nearer the shore than any of the others had ventured to do; nay, she even went up the narrow canal, under the handsome marble balcony that threw its long shadow over the water. Here she would sit, and gaze at the young prince, who thought himself quite alone in the bright moonshine.

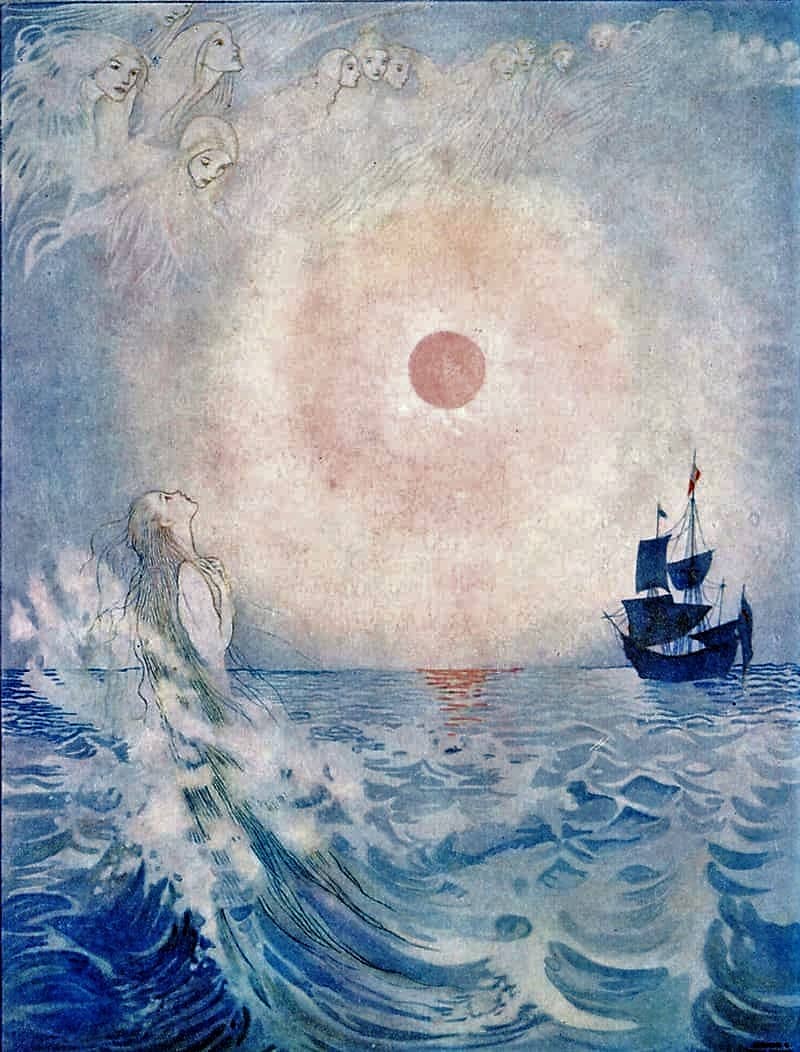

Many an evening did she see him sailing in his pretty boat, adorned with flags, and enjoying music: then she would listen from amongst the green reeds; and if the wind happened to seize hold of her long silvery-white veil, those who saw it took it to be a swan spreading out his wings.

Many a night, too, when fishermen were spreading their nets by torchlight, she heard them speaking highly of the young prince; and she rejoiced that she had saved his life, when he was tossed about, half dead, on the waves. And she remembered how his head had rested on her bosom, and how heartily she had kissed him—but of all this, he knew nothing, and he could not even dream about her.

She soon grew to be more and more fond of human beings, and to long more and more fervently to be able to walk about amongst them, for their world appeared to her far larger and more beautiful than her own. They could fly across the sea upon ships, and scale mountains that towered above the clouds; and the lands they possessed—their fields and their forests—stretched away far beyond the reach of her sight.

There was such a deal that she wanted to learn, but her sisters were not able to answer all her questions; therefore she applied to her old grandmother, who was well acquainted with the upper world, which she called, very correctly, the lands above the sea.

“If human beings do not get drowned,” asked the little mermaid, ” can they live forever? Do not they die, as we do here in the sea?”

“Yes,” said the ancient dame, “they must die as well as we; and the term of their life is even shorter than ours. We can live to be three hundred years old; but when we cease to be here, we shall only be changed into foam, and are not even buried below among those we love. Our souls are not immortal. We shall never enter upon a new life. We are like the green reed, that can never flourish again when it has once been cut through. Human beings, on the contrary, have a soul that lives eternally—yea, even after the body has been committed to the earth—and that rises up through the clear pure air to the bright stars above! Like as we rise out of the water to look at the haunts of men, so do they rise to unknown and favoured regions, that we shall never be privileged to see.”

“And why have not we an immortal soul?” asked the little mermaid sorrowfully. “I would willingly give all the hundreds of years I may have to live, to be a human being but for one day, and to have the hope of sharing in the joys of the heavenly world.”

“You must not think about that,” said the old dame. “We feel we are much happier and better than the human race above.”

“So I shall die, and be driven about like foam on the sea, and cease to hear the music of the waves, and to see the beautiful flowers, and the red sun? Is there nothing I can do to obtain an immortal soul?”

“No,” said the old sea queen; “unless a human being loved you so dearly that you were more to him than either father or mother; if all his thoughts and his love were centred in you, and he allowed the priest to lay his right hand in yours, promising to be faithful to you here and hereafter: then would his soul glide into your body, and you would obtain a share in the happiness awaiting human beings. He would give you a soul without forfeiting his own. But this will never happen! Your fish’s tail, which is a beauty amongst us sea-folk, is thought a deformity on earth because they know no better. It is necessary there to have two stout props, that they call legs, in order to be beautiful!”

The little mermaid sighed as she cast a glance at her fish’s tail.

“Let us be merry,” said the old dame; “let us jump and hop about during the three hundred years that we have to live—which is really quite enough, in all conscience. We shall then be all the more disposed to rest at a later period. Tonight we shall have a court ball.”

On these occasions, there was a display of magnificence such as we never see upon earth. The walls and the ceiling of the large ball-room were of thick, though transparent glass, hundreds of colossal mussel shells—some of a deep red, others as green as grass—were hung in rows on each side, and contained blue flames, that illuminated the whole room, and shone through the walls, that the sea was lighted all around. Countless fishes, great and small, were to be seen swimming past the glass walls, some of them flaunting scarlet scales, while others sparkled like liquid gold or silver.

Through the ballroom flowed a wide stream, on whose surface the mermen and mermaids danced to their own sweet singing. Human beings have no such voices. The little mermaid sang the sweetest of them all, and the whole court applauded with their hands and tails; and for a moment she felt delighted, for she knew that she had the loveliest voice ever heard upon earth or upon the sea. But her thoughts soon turned once more to the upper world, for she could not long forget either the handsome prince or her grief at not having an immortal soul like his. She, therefore, stole out of her father’s palace, where all within was song and festivity, and sat down sadly in her own little garden. Here she heard a bugle sounding through the water.

“Now,” thought she, “he is surely sailing about up above—he who incessantly fills all my thoughts, and to whose hands I would fain entrust the happiness of my existence. I will venture everything to win him and to obtain an immortal soul. While my sisters are dancing yonder in my father’s castle, I will go to the sea witch, who has always frightened me hitherto, but now, perhaps, she can advise and help me.”

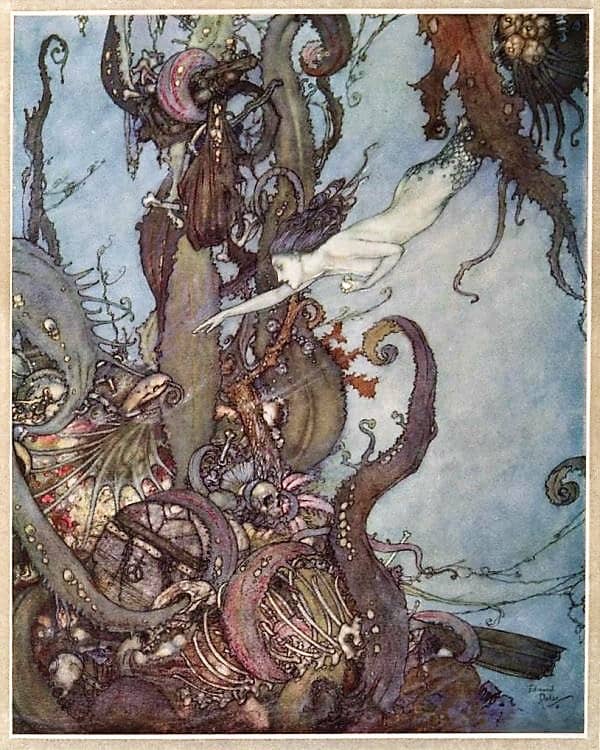

The little mermaid then left her garden and repaired to the rushing whirlpool, behind which the sorceress lived. She had never gone that way before. Neither flowers nor seagrass grew there; and nothing but bare, grey, sandy ground led to the whirlpool, where the waters kept eddying like waving mill wheels, dragging everything they clutched hold of into the fathomless depth below. Between these whirlpools, that might have crushed her in their rude grasp, was the mermaid forced to pass to reach the dominions of the sea-witch; and even here, during a good part of the way, there was no other road than across a sheet of warm, bubbling mire, which the witch called her turf-common. At the back of this lay her house, in the midst of a most singular forest. Its trees and bushes were polypi—half animal, half plant—they looked like hundred-headed serpents growing out of the ground; the branches were long, slimy arms, with fingers like flexible worms, and they could move every joint from the root to the tip. They laid fast hold of whatever they could snatch from the sea and never yielded it up again. The little mermaid was so frightened at the sight of them that her heart beat with fear, and she was fain to turn back, but then she thought of the prince, and of the soul that human beings possessed, and she took courage.

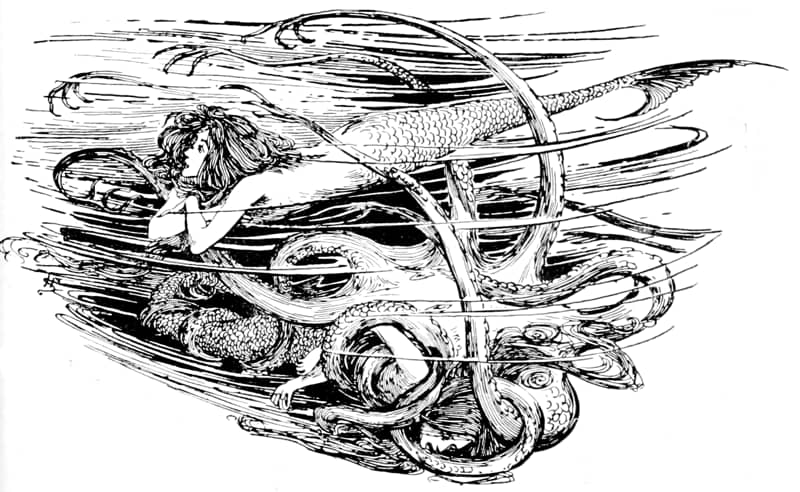

She knotted up her long, flowing hair, so that the polypi might not seize hold of her locks; and, crossing her hands over her bosom, she darted along, as a fish shot through the water, between the ugly polypi, that stretched forth their flexible arms and fingers behind her. She perceived how each of them retained what it had seized, with hundreds of little arms, as strong as iron clasps. Human beings, who had died at sea and had sunk below, looked like white skeletons in the arms of the polypi. They clutched rudders, too, and chests, and skeletons of animals belonging to the earth, and even a little mermaid whom they had caught and stifled—and this appeared to her, perhaps, the most shocking of all.

She now approached a vast swamp in the forest, where large, fat water snakes were wallowing in the mire and displaying their ugly whitish-yellow bodies. In the midst of this loathsome spot stood a house, built of the bones of shipwrecked human beings, and within sat the sea witch, feeding a toad from her mouth, just as people amongst us give a little canary bird a lump of sugar to eat. She called the nasty fat water snakes her little chicks, and let them creep all over her bosom.

“I know what you want!” said the sea witch. “It is very stupid of you, but you shall have your way, as it will plunge you into misfortune, my fair princess. You want to be rid of your fish’s tail, and to have a couple of props like those human beings have to walk about upon, in order that the young prince may fall in love with you, and that you may obtain his hand and an immortal soul into the bargain!” And then the old witch laughed so loud and so repulsively that the toad and the snakes fell to the ground, where they lay wriggling about.

“You come just at the nick of time,” added the witch, “for tomorrow, by sunrise, I should no longer be able to help you till another year had flown past. I will prepare you a potion; and you must swim ashore with it tomorrow, before sunrise, and then sit down and drink it. Your tail will then disappear, and shrivel up into what human beings call neat legs. But mind, it will hurt you as much as if a sharp sword were thrust through you. Everybody that sees you will say you are the most beautiful mortal ever seen. You will retain the floating elegance of your gait: no dancer will move so lightly as you, but every step you take will be like treading upon such sharp knives that you would think your blood must flow. If you choose to put up with sufferings like these, I have the power to help you.”

“I do,” said the little mermaid, in a trembling voice, as she thought of the prince and of an immortal soul.

“But think you well,” said the witch; “if once you obtain a human form, you can never be a mermaid again! You will never be able to dive down into the water to your sisters or return to your father’s palace; and if you should fail in winning the prince’s love to the degree of his forgetting both father and mother for your sake, and loving you with his whole soul, and bidding the priest join your hands in marriage, then you will never obtain an immortal soul! And the very day after he will have married another, your heart will break, and you will dissolve into the foam on the billows.”

“I am resolved,” said the little mermaid, who had turned as pale as death.

“But you must pay me my dues,” said the witch, “and it is no small matter I require. You have the loveliest voice of all the inhabitants of the deep, and you reckon upon its tones to charm him into loving you. Now, you must give me this beautiful voice. I choose to have the best of all you possess in exchange for my valuable potion. For I must mix my own blood with it, that it may prove as sharp as a two-edged sword.”

“But if you take away my voice,” said the little mermaid, “what have I left?”

“Your lovely form,” said the witch, “your buoyant carriage, and your expressive eyes. With these, you surely can befool a man’s heart. Well? Has your courage melted away? Come, put out your little tongue, and let me cut it off for my fee, and you shall have the valuable potion.”

“So be it,” said the little mermaid; and the witch put her cauldron on the fire to prepare the potion. “Cleanliness is a virtue!” quoth she, scouring the cauldron with the snakes that she had tied into a knot; after which she pricked her own breast, and let her black blood trickle down into the vessel. The steam rose up in such fanciful shapes that no one could have looked at them without a shudder. The witch kept flinging fresh materials into the cauldron every moment, and when it began to simmer it was like the wailings of a crocodile. At length the potion was ready, and it looked like the purest spring water.

“Here it is,” said the witch, cutting off the little mermaid’s tongue; so now she was dumb and could neither sing nor speak.

“If the polypi should seize hold of you on your return through my forest,” said the witch, “you need only sprinkle a single drop of this potion over them, and their arms and fingers will have shivered to a thousand pieces.” But the little mermaid had no need of this talisman; the polypi drew back in alarm from her on perceiving the dazzling potion that shined in her hand like a twinkling star. So she crossed rapidly through the forest, the swamp, and the raging whirlpool.

Continued..