- The Little Mermaid (Original) – Part I

- The Little Mermaid (Original) – Part II

- The Little Mermaid (Original) – Part III

- The Little Mermaid (Original) – Part IV

She saw her father’s palace—the torches were now extinguished in the large ballroom—and she knew the whole family were asleep within, but she did not dare venture to go and seek them, now that she was dumb and was about to leave them forever. Her heart seemed ready to burst with anguish. She stole into the garden and plucked a flower from each of her sisters’ flower beds, kissed her hand a thousand times to the palace, and then rose up through the blue waters.

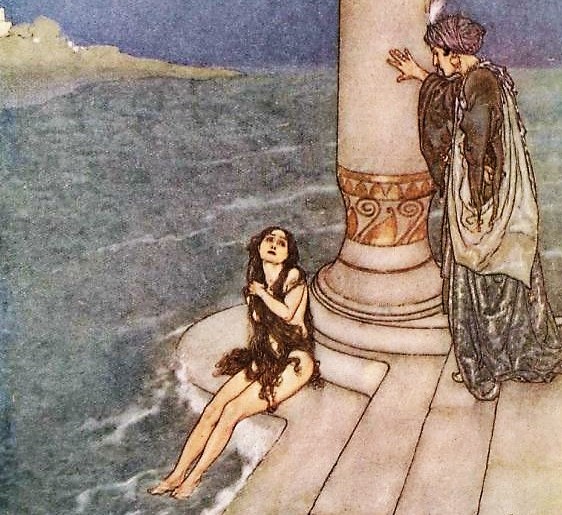

The sun had not yet risen when she saw the prince’s castle and reached the magnificent marble steps. The moon shone brightly. The little mermaid drank the sharp and burning potion, and it seemed as if a two-edged sword was run through her delicate frame. She fainted away and remained apparently lifeless. When the sun rose over the sea she awoke, and felt a sharp pang; but just before she stood the handsome young prince. He gazed at her so intently with his coal-black eyes that she cast hers to the ground, and now perceived that her fish’s tail had disappeared and that she had a pair of the neatest little white legs that a maiden could desire. Only, having no clothes on, she was obliged to enwrap herself in her long, thick hair.

The prince inquired who she was, and how she had come thither; but she could only look at him with her mild but sorrowful deep blue eyes, for speak she could not. He then took her by the hand and led her into the palace. Every step she took was, as the witch had warned her it would be, like treading on the points of needles and sharp knives; but she bore it willingly, and, hand in hand with the prince, she glided in as lightly as a soap-bubble, so that he, as well as everybody else, marvelled at her lovely lightsome gait.

She was now dressed in costly robes of silk and muslin and was the most beautiful of all the inmates of the palace, but she was dumb and could neither sing nor speak. Handsome female slaves, attired in silk and gold, came and sang before the prince and his royal parents; and one of them happened to sing more beautifully than all the others, the prince clapped his hands and smiled. This afflicted the little mermaid. She knew that she herself had sung much more exquisitely, and thought, “Oh, did he but know that to be near him I sacrificed my voice to all eternity!”

The female slaves now performed a variety of elegant, aerial-looking dances to the sound of the most delightful music. The little mermaid then raised her beautiful white arms, stood on the tips of her toes, and floated across the floor in such a way as no one had ever danced before. Every motion revealed some fresh beauty, and her eyes appealed still more directly to the heart than the singing of the slaves had done.

Everybody was enchanted, but most of all the prince, who called her his little foundling; and she danced on and on, though every time her foot touched the floor she felt as if she were treading on sharp knives. The prince declared that he would never part with her, and she obtained leave to sleep on a velvet cushion before his door.

He had her dressed in male attire so that she might accompany him on horseback. They then rode together through the perfumed forests, where the green boughs touched their shoulders, and the little birds sang amongst the cool leaves. She climbed up mountains by the prince’s side; and though her tender feet bled so that others perceived it, she only laughed at her sufferings, and followed him till they could see the clouds rolling beneath them like a flock of birds bound for some distant land.

At night, when others slept throughout the prince’s palace, she would go and sit on the broad marble steps, for it cooled her burning feet to bathe them in the seawater; and then she thought of those below the deep.

One night her sisters rose up arm in arm and sang so mournfully as they glided over the waters. She then made them a sign, when they recognised her and told her how deeply she had afflicted them all. After that they visited her every night; and once she perceived at a great distance her aged grandmother, who had not come up above the surface of the sea for many years, and the sea king, with his crown on his head. They stretched out their arms to her, but they did not venture so near the shore as her sisters.

Each day she grew to love the prince more fondly; and he loved her just as one loves a dear, good child. But as to choosing her for his queen, such an idea never entered his head; yet, unless she became his wife, she would not obtain an immortal soul and would melt to foam on the morrow of his wedding another.

“Don’t you love me the best of all?” would the little mermaid’s eyes seem to ask, when he embraced her and kissed her fair forehead.

“Yes, I love you best,” said the prince, “for you have the best heart of any. You are the most devoted to me, and you resemble a young maiden whom I once saw, but whom I shall never meet again. I was on board a ship that sank; the billows cast me near a holy temple, where several young maids were performing divine service; the youngest of them found me on the shore and saved my life. I saw her only twice. She would be the only one that I could love in this world, but your features are like hers, and you have almost driven her image out of my soul. She belongs to the holy temple; and, therefore, my good star has sent you to me—and we will never part.”

“Alas! he knows not that it was I who saved his life!” thought the little mermaid. “I bore him across the sea to the wood where stands the holy temple, and I sat beneath the foam to watch whether any human beings came to help him. I saw the pretty girl whom he loves better than he does me.” And the mermaid heaved a deep sigh, for tears she had none to shed.

He says the maiden belongs to the holy temple, and she will, therefore, never return to the world. They will not meet again while I am by his side and see him every day. I will take care of him, love him, and sacrifice my life to him.”

But now came a talk of the prince being about to marry, and to obtain for his wife the beautiful daughter of a neighbouring king; and that was why he was fitting out such a magnificent vessel. The prince was travelling ostensibly on a mere visit to his neighbour’s estates, but in reality to see the king’s daughter. He was to be accompanied by a numerous retinue.

The little mermaid shook her head and smiled. She knew the prince’s thoughts better than the others did. “I must travel,” he had said to her. “I must see this beautiful princess because my parents require it of me, but they will not force me to bring her home as my bride. I cannot love her. She will not resemble the beautiful maid in the temple whom you are like; and if I were compelled to choose a bride, it should sooner be you, my dumb foundling, with those expressive eyes of yours.” And he kissed her rosy mouth and played with her long hair, and rested his head against her heart, which beat high with hopes of human felicity and of an immortal soul.

“You are not afraid of the sea, my dumb child, are you?” said he, as they stood on the magnificent vessel that was to carry them to the neighbouring king’s dominions. And he talked to her about tempests and calm, of the singular fishes to found in the deep, and of the wonderful things the divers saw below; and she smiled, for she knew better than anyone else what was in the sea below.

During the moonlit night, when all were asleep on board, not even excepting the helmsman at his rudder, she sat on the deck, gazed through the clear waters, and fancied she saw her father’s palace. High above it stood her aged grandmother, with her silver crown on her head, looking up intently at the keel of the ship. Then her sisters rose to the surface and gazed at her mournfully, and wrung their white hands. She made a sign to them, smiled, and would fain have told them that she was happy and well off; but the cabin boy approached, and the sisters dived beneath the waves, leaving him to believe that the white forms he thought he described were only the foam upon the waters.

The next morning the ship came into port, at the neighbouring king’s splendid capital. The bells were all set a-ringing, trumpets sounded flourishes from high turrets, and soldiers, with flying colours and shining bayonets, stood ready to welcome the stranger. Every day brought some fresh entertainment: balls and feasts succeeded each other. But the princess was not yet there; for she had been brought up, people said, in a far distant, holy temple, where she had acquired all manner of royal virtues. At last, she came.

The little mermaid was curious to judge her beauty, and she was obliged to acknowledge to herself that she had never seen a lovelier face. Her skin was delicate and transparent, and beneath her long, dark lashes sparkled a pair of sincere, dark blue eyes.

“It is you!” cried the prince—”you who saved me, when I lay like a lifeless corpse upon the shore!” And he folded his blushing bride in his arms. “Oh, I am too happy!” said he to the little mermaid: “My fondest dream has come to pass. You will rejoice at my happiness, for you wish me better than any of them.” And the little mermaid kissed his hand and felt already as if her heart was about to break. His wedding morning would bring her death, and she would be then changed to foam upon the sea.

All the church bells were ringing, and the heralds rode through the streets and proclaimed the approaching nuptials. Perfumed oil was burning in costly silver lamps on all the altars. The priests were swinging their censers; while the bride and bridegroom joined their hands, and received the bishop’s blessing. The little mermaid, dressed in silk and gold, held up the bride’s train; but her ears did not hear the solemn music, neither did her eyes behold the ceremony: she thought of the approaching gloom of death, and of all she had lost in this world.

That same evening the bride and bridegroom went on board. The cannons were roaring, the banners were streaming, and a costly tent of gold and purple, lined with beautiful cushions, had been prepared on deck for the reception of the bridal pair. The vessel then set sail, with a favourable wind, and glided smoothly along the calm sea.

When it grew dark, a number of variegated lamps were lighted, and the crew danced merrily on the deck. The little mermaid could not help remembering her first visit to the earth, when she witnessed similar festivities and magnificence; and she twirled round in the dance, half poised in the air, like a swallow when pursued; and all present cheered her in ecstasies, for never had she danced so enchantingly before. Her tender feet felt the sharp pangs of knives; but she heeded it not, for a sharper pang had shot through her heart. She knew that this was the last evening she should ever be able to see him for whom she had left both her relations and her home, sacrificed her beautiful voice, and daily suffered most excruciating pains, without his having even dreamed that such was the case. It was the last night on which she might breathe the same air as he, and gaze on the deep sea and the starry sky.

An eternal night, unenlivened by either thoughts or dreams, now awaited her; for she had no soul, and could never now obtain one. Yet all was joy and gaiety on board till long past midnight; and she was fain to laugh and dance, though the thoughts of death were in her heart. The prince kissed his beautiful bride, and she played with his black locks; and then they went, arm in arm, to rest beneath the splendid tent.

All was now quiet on board; the steersman only was sitting at the helm, as the little mermaid leaned her white arms on the edge of the vessel, and looked towards the east for the first blush of morning. The very first sunbeam, she knew, must kill her. She then saw her sisters rising out of the flood.

They were as pale as herself, and their long and beautiful locks were no longer streaming to the winds, for they had been cut off. “We gave them to the witch,” said they, “to obtain help, that you might not die tonight. She gave us a knife in exchange—and a sharp one it is, as you may see. Now, before sunrise, you must plunge it into the prince’s heart; and when his warm blood shall besprinkle your feet, they will again close up into a fish’s tail, and you will be a mermaid once more, and can come down to us, and live out your three hundred years, before you turn into inanimate, salt foam. Haste, then! He or you must die before sunrise! Our old grandmother has fretted till her white hair has fallen off, as ours has under the witch’s scissors. Haste, then! Do you not perceive those red streaks in the sky? In a few minutes, the sun will rise, and then you must die!” And they then fetched a deep, deep sigh, as they sank down into the waves.

The little mermaid lifted the scarlet curtain of the tent, and beheld the fair bride resting her head on the prince’s breast; and she bent down and kissed his beautiful forehead, then looked up at the heavens, where the rosy dawn grew brighter and brighter; then gazed on the sharp knife, and again turned her eyes towards the prince, who was calling his bride by her name in his sleep. She alone filled his thoughts, and the mermaid’s fingers clutched the knife instinctively—but in another moment she hurled the blade far away into the waves, that gleamed redly where it fell, as though drops of blood were gurgling up from the water.

She gave the prince one last, dying look, and then jumped overboard, and felt her body dissolving into foam.

The sun now rose out of the sea; its beams threw a kindly warmth upon the cold foam, and the little mermaid did not experience the pangs of death. She saw the bright sun and above were floating hundreds of transparent, beautiful creatures; she could still catch a glimpse of the ship’s white sails, and of the red clouds in the sky, across the swarms of these lovely beings. Their language was melody, but too ethereal to be heard by human ears, just as no human eye can discern their forms. Though without wings, their lightness poised them in the air. The little mermaid saw that she had a body like theirs, that kept rising higher and higher from out the foam.

“Where am I?” asked she! and her voice sounded like that of her companions—so ethereal that no earthly music could give an adequate idea of its sweetness.

“Amongst the daughters of the air!” answered they. “A mermaid has not an immortal soul, and cannot obtain one, unless she wins the love of some human being—her eternal welfare depends on the will of another. But the daughters of the air, although not possessing an immortal soul by nature, can obtain one by their good deeds. We fly to warm countries, and fan the burning atmosphere, laden with pestilence, that destroys the sons of man. We diffuse the perfume of flowers through the air to heal and to refresh. When we have striven for three hundred years to do all the good in our power, we then obtain an immortal soul, and share in the eternal happiness of the human race. You, poor little mermaid! have striven with your whole heart like ourselves. You have suffered and endured, and have raised yourself into an aerial spirit, and now your own good works may obtain you an immortal soul after the lapse of three hundred years.”

And the little mermaid lifted her brightening eyes to the sun, and for the first time she felt them filled with tears. All was now astir in the ship, and she could see the prince and his beautiful bride looking for her, and then gazing sorrowfully at the pearly foam, as though they knew that she had cast herself into the waves. She then kissed the bride’s forehead, and fanned the prince, unseen by either of them, and then mounted, together with the other children of the air, on the rosy cloud that was sailing through the atmosphere.

“Thus shall we glide into the Kingdom of Heaven, after the lapse of three hundred years,” said she.

“We may reach it sooner,” whispered one of the daughters of the air. “We enter unseen the dwellings of man, and for each day on which we have met with a good child, who is the joy of his parents, and deserving of their love, the Almighty shortens the time of our trial. The child little thinks, when we fly through the room, and smile for joy at such a discovery, that a year is deducted from the three hundred we have to live. But when we see an ill-behaved or naughty child, we shed tears of sorrow, and every tear adds a day to the time of our probation.”